Ancient protein analysis

How can 8000-year-old unwashed dishes be used to reveal the diets of ancient populations?

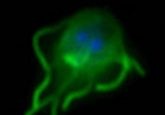

The new field of palaeoproteomics uses cutting-edge techniques to analyze ancient proteins, which are preserved 10-times longer than DNA. The development of new technologies has enabled their study, with the possibility that trace amounts of proteins can be identified.

This has allowed a better insight into the evolution of extinct species and chronic diseases, as well as the reconstruction of ancient human diets.

Unraveling an 8000 year-old mystery

Archeologist Eva Rosenstock (Institute of Prehistoric Archaeology; Berlin, Germany) was a principal investigator in the famous Neolithic town of Çatahöyük (Anatolia, Turkey) in which the population appeared to have declined and disappeared entirely in approximately5700 BC.

The west mound area of the town was rife with pottery and ceramics. Rosenstock found this mostly uninteresting, until another researcher discovered calcified deposits inside the ceramic vessels. This would have been considered a product of the environment if not for the fact that the deposits were found exclusively on the inside of the vessels.

“It was really clear that this must have to do with the stuff that was inside this bowl,” commented Rosenstock.

To reveal more about these deposits, Rosenstock reached out to Jessica Hendy (then University of York, UK, now Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History; Munich, Germany) whose work focused on the extraction and analysis of proteins from fossilized teeth to learn more about the diets of ancient populations. Hendy believed she could apply these same methods to extract proteins from the insides of the ceramic vessels.

The results of this work, published recently in Nature Ecology and Evolution, reveal just how far protein analysis methods have come. In order to carry out the work, samples were put through a mass spectrometer and then compared to databases of known proteins. This is different from past analyses, which have looked for specific proteins instead of using a ‘shotgun’ approach.

“This is the oldest successful use of protein analysis to study foods in pottery that I’m aware of,” said Hendy. “What’s particularly significant is the level of detail we were able to see from the culinary practices of this early farming community.”

They discovered proteins from plants, including barley, wheat and peas, and the blood and milk of different animals, including cows, sheep and goats. The researchers were able to visualize the proteins with an incredible level of detail, even distinguishing milk whey from liquid. This provided them with the insight that this ancient population was potentially producing cheese or yogurt.

“Here we have the earliest insight into people doing this kind of milk processing,” commented Hendy. “Researchers have found milk in pottery in earlier times, but what’s exciting about this find and this technique is that we can see actually how people are processing their dairy foods, rather than simply detecting its presence or absence.”

The team believes that the survival of the proteins is due to the protection provided by limescale build up. However, it is still unknown just how long these proteins can survive. Rosenstock and Hendy now hope to uncover even more detail about the diets of not only ancient humans in Çatahöyük, but also societies across the world.

Setting standards

Hendy is one of the researchers at the leading edge in the study of ancient proteins. As with all new fields of research, palaeoproteomics was in desperate need of standards and faced the challenges of a lacking consistency in data reporting and procedures to avoid contamination, to name a few. This has now led to the publication of “A guide to ancient protein studies” in Nature Communications.

“Palaeoproteomics holds enormous potential to dramatically expand archaeological, palaeontological and evolutionary research,” explained Hendy, co-lead author of this recent publication. “It is crucial that the discipline hold itself to high standards in order to ensure that it is able to meet this potential.”

Hendy, along with a team of researchers from across the leading institutions for the study of ancient proteins, set about to put forward the ‘best practices’ for the study, analysis and reporting of ancient protein research. The team stress that these guidelines are not rigid, instead seeking to consolidate and strengthen the field.

“Undoubtedly, as new laboratory and statistical strategies for characterizing proteins emerge, these guidelines will require debate within the community and further updating,” commented co-lead author Frido Welker (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology; Munich, Germany). “However, we hope that the standards of practice presented here will help to provide a firm foundation for palaeoproteomics as a technique for use in a variety of fields.”

Not only can the analysis of ancient proteins reveal more clues about the evolution of humankind and their past behaviors, but it also has the power to reveal the answers to many ancient mysteries. Now, with the publication of standards, this will only see the field go from strength to strength.