Acetates: the new culprit for alcohol-related gut bacterial overgrowth

Metabolites of ethanol have been found to be responsible for the overgrowth of gut bacteria displayed in patients with alcoholic liver disease.

The effects of chronic alcohol use in most organs are well understood, and its effect on the liver can be particularly devastating. Around 30,000 Americans die every year from alcoholic liver diseases. The effects of alcohol on the lower intestine, however, have remained elusive.

Our lower intestines are home to an entire ecosystem of bacteria. Like any ecosystem, the balance of life can be influenced significantly by external pressures. The consumption of alcohol has been demonstrated to greatly alter the growth rate of gut microbiota, but the mechanism of this effect has eluded researchers until now.

Alcohol, when consumed, is mainly absorbed in the mouth and the stomach and very little makes its way to the intestines. A new study from researchers at the University of California San Diego (CA, USA) proposes that it is a metabolite of the alcohol we drink that is the root cause of this hitherto unexplained change in our gut bacteria [1]. Their initial hypothesis was that alcohol caused lower expression of an intrinsic antibiotic regulator in the intestine; however, this was disproven in an earlier mouse model study [2].

Why do some T cells stay in the gut?

Why do some T cells stay in the gut?

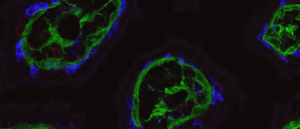

Researchers find out what keeps T cells patrolling the gut by decoding their communication with epithelial cells.

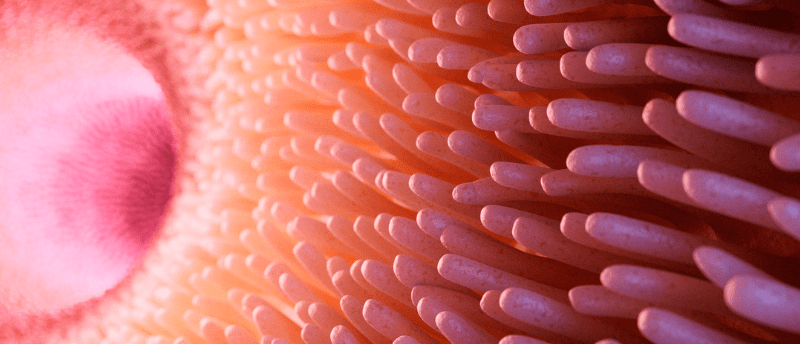

In a cascading enzymatic process, our livers oxidize ethanol, first to acetaldehyde and then to salts of acetic acid known as acetates. Acetates in the blood can then diffuse back into the intestines, where they can be absorbed by bacteria. To demonstrate this, the researchers fed mice isotopically enriched ethanol, allowing them to monitor its metabolic pathways and distribution in vivo. The effect of ethanol on gut bacterial growth in mice was exhibited to be similar to feeding mice acetates directly. However, acetate feeding presented no liver damage associated with alcohol.

Going further, the team used metatranscriptomic analysis to monitor what proteins the bacteria were expressing to metabolize either ethanol or acetates. They found that there was no change in expression for enzymes that use ethanol as a substrate, but gene expression for enzymes that metabolize acetates were upregulated. This means that gut bacteria are unable to use ethanol directly as a food source and instead use acetates.

“You can think of this a bit like dumping fertilizer on a garden,” explained senior author Karsten Zengler. “The result is an explosion of imbalanced biological growth, benefitting some species but not others.”

Conclusions that can be drawn from this study are limited in the short term. However, this study has advanced our understanding of the link between bacterial overgrowth and chronic alcohol consumption. As described by Zengler, “These findings suggest that microbial ethanol metabolism does not contribute significantly to gut microbiome dysbiosis (imbalance) and that the microbiome altered by acetate does not play a major role in liver damage.”