How cells stop lysosomes from leaking

Original story from Umeå University (Sweden).

The mechanism by which cells detect leaky lysosomes has been revealed, laying the groundwork for new treatments for diseases where lysosomal damage plays a central role.

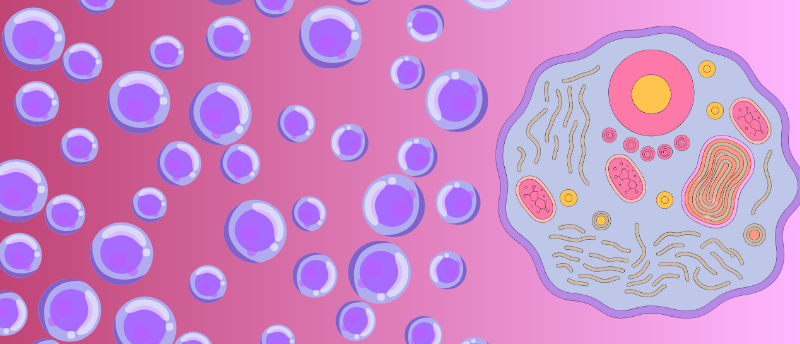

When the cell’s recycling stations, the lysosomes, start leaking, it can become dangerous. Toxic waste risks spreading and damaging the cell. Now, researchers at Umeå University (Sweden) have revealed the molecular sensors that detect tiny holes in lysosomal membranes so they can be quickly repaired – a process crucial for preventing inflammation, cell death and diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Lysosomes are the cell’s recycling stations, handling cellular waste and converting it into building blocks that can be reused. Lysosomal membranes are frequently exposed to stress from pathogens, proteins and metabolic byproducts. Damage can lead to leakage of toxic contents into the cytoplasm, which in turn may cause inflammation and cell death. Until now, the mechanism by which cells detect these membrane injuries has remained unknown.

In a recently published study, professor Yaowen Wu and his research group at the Department of Chemistry at Umeå University, identified the signaling pathway that is activated in response to lysosomal damage. This discovery laid the foundation for understanding how the cell senses membrane injuries.

Sensors identified

In the new study, the researchers take it a step further and have discovered two autophagy protein complexes that serve as the long-sought sensors of lysosomal damage.

“They respond and quickly move to the damaged membranes when protons or calcium leak out, initiating the repair system that seals the hole. We observed that without these two key proteins, the cell fails to repair the damage, causing the lysosome to rupture,” explained Yaowen Wu, lead author of the study.

Longevity lingers in the lysosome

Changes in Caenorhabditis elegans lysosome metabolism can be carried through generations via inherited histone modifications.

Combination of techniques

The team used a combination of live-cell imaging, genetic knockout models, advanced microscopy, and functional repair assays to map the sequence of events following controlled lysosomal damage.

The results apply to several different types of cells and show the same underlying mechanism.

Next step in research

“The discovery provides a new understanding and opens the door to new treatment strategies for diseases where lysosomal damage plays a central role. In future studies, we will investigate links to neurodegeneration, infections and inflammation,” commented Yaowen Wu.

Dale Corkery, staff scientist and first author, added:

“It is vital that lysosomal contents stay where they belong. If we understand why leaks sometimes go undetected, we can also understand why cells die in neurodegenerative diseases.”

This article has been republished from the following materials. Material may have been edited for length and house style. For further information, please contact the cited source. Our press release publishing policy can be accessed here.