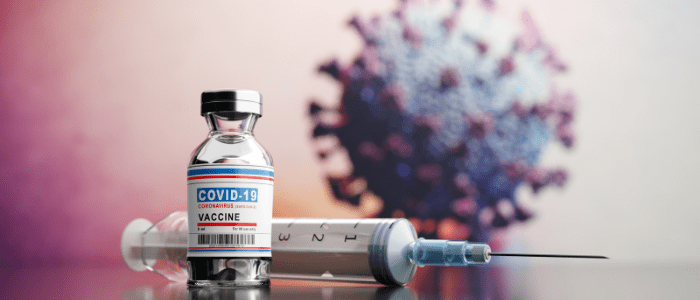

What effect will SARS-CoV-2 variants have on vaccine efficacy?

The ‘inevitable’ domination of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants from Brazil, South Africa and the UK could result in less effective COVID-19 vaccines and drugs, designed with the original virus form in mind.

Researchers from Washington University School of Medicine (MO, USA) have published a study indicating that novel SARS-CoV-2 variants can evade antibodies that target the original form of the virus. The study discovered that more antibodies are needed to neutralize these variants, regardless of the antibody origin – from vaccination, natural infection, or therapeutic antibodies, with few exceptions.

Panel discussion: Immunology, from cancer to COVID-19

Our panelists will discuss vaccine development, addressing unknowns in immune response and leveraging the immune system in disease treatment.

This also implies that vaccines and drugs that were designed based on the original virus form could be less effective against COVID-19 as the new variants become the dominant forms, which experts have labeled as inevitable.

“We’re concerned that people whom we’d expect to have a protective level of antibodies because they have had COVID-19 or been vaccinated against it, might not be protected against the new variants,” commented senior author Michael Diamond.

“There’s wide variation in how much antibody a person produces in response to vaccination or natural infection. Some people produce very high levels, and they would still likely be protected against the new, worrisome variants. But some people, especially older and immunocompromised people, may not make such high levels of antibodies. If the level of antibody needed for protection goes up tenfold, as our data indicate it does, they may not have enough. The concern is that the people who need protection the most are the ones least likely to have it.”

To date, vaccine developers have heavily focused their tactics on targeting SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein. All three vaccines that are currently approved for use by the US FDA – the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines – have been designed with an anti-spike protein approach.

The novel variants – from the UK (B.1.1.7), South Africa (B.1.135) and Brazil (B.1.1.248) – all have multiple mutations in the spike protein. As part of the team’s investigations, they created viruses with single mutations to measure the effect of each mutation on the effectiveness of antibodies. They discovered one mutation – a single amino acid replacement, named E484K – was the cause of most variation in antibody effectiveness.

The South African and Brazilian variants both had this mutation, whereas the UK variant did not. The researchers used antibodies from blood samples of humans who had natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2, humans who had been given the Pfizer vaccine and animal models who had been given an experimental vaccine that is administered through nasal delivery.

While the UK variant was neutralized with comparable levels of antibodies as was used for the original SARS-CoV-2 form, the Brazilian and South African variants required between 3.5- and 10-times as much antibody for neutralization.

“We don’t exactly know what the consequences of these new variants are going to be yet,” explained Diamond.

“Antibodies are not the only measure of protection; other elements of the immune system may be able to compensate for increased resistance to antibodies. That’s going to be determined over time, epidemiologically, as we see what happens as these variants spread. Will we see reinfection? Will we see vaccines lose efficacy and drug resistance emerge? I hope not. But it’s clear that we will need to continually screen antibodies to make sure they’re still working as new variants arise and spread and potentially adjust our vaccine and antibody-treatment strategies.”