Developing diagnostics for ATTR amyloidosis with cryo-EM

Lorena Saelices Gómez is a Principal Investigator at UT Southwestern (TX, USA), whose research group focuses on transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis) and other amyloid diseases. After earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Sevilla (Spain), Saelices Gómez applied her training in molecular biology and structural biology as a postdoc studying proteins involved in human amyloid disease.

Lorena Saelices Gómez is a Principal Investigator at UT Southwestern (TX, USA), whose research group focuses on transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis) and other amyloid diseases. After earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Sevilla (Spain), Saelices Gómez applied her training in molecular biology and structural biology as a postdoc studying proteins involved in human amyloid disease.

Annie Coulson, our Digital Editor, found out more about Saelices Gómez’s research into amyloid diseases and the techniques they use to develop diagnostics and other clinical tools.

Could you explain the focus of your research?

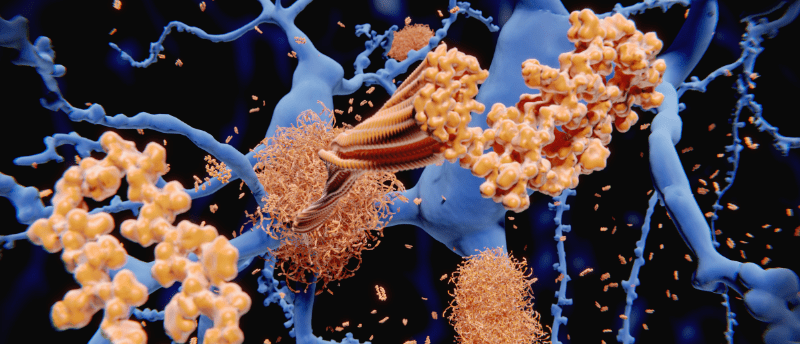

In our laboratory, we study the root cause of a cardiac disease known as ATTR amyloidosis as well as other related diseases. ATTR amyloidosis is a fatal cardiac disease that is caused by the build-up of amyloid proteins throughout the body. This build-up leads to a complex variety of symptoms, including diarrhea, nausea, and muscle weakness, which makes it really difficult to diagnose.

Although not widely known by non-specialists, ATTR amyloidosis is estimated to affect more than 2 million people in the US, including 25% of people over 80 years old and 4% of African Americans who carry a mutation that leads to this disease. Although there are several treatments that can stop the progression of the disease, they only work when given at early stages so developing effective diagnostics is crucial. Our work on ATTR amyloidosis closes the gap between basic science and the clinic by using the molecular structures of the disease agent to develop technologies for the diagnosis and treatment of affected individuals.

In our laboratory, we use a very powerful microscope, a cryogenic electron microscope, that can give us pictures of the tiny molecules that cause this disease. With these pictures, and many hours analyzing them on a computer, we obtain the structures of these pathogenic molecules. We then use these structures to design therapeutics and diagnostic tools. We have recently developed a specific test that can detect this disease with only a few drops of blood. We are moving towards bringing our technology to the clinic soon.

What inspired you to study amyloid structures and Alzheimer’s?

My grandmother passed away after 15 years of suffering from Alzheimer’s disease; I do not remember her with full cognitive capabilities. She lived with us during her most difficult years, and I had to help my mother take care of her daily. This experience marked me tremendously. Not only because of how hard it is to see someone you love living with this devastating disease, but also because it was (and still is) so poorly understood.

When I started my career, I felt inclined to study the process that leads to this disease, but I did not have the chance to do so until I started my postdoctoral studies in the laboratory of David Eisenberg at UCLA (CA, USA). There, I was assigned a project to study protein aggregation associated with ATTR amyloidosis. Although the focus of the Eisenberg lab was neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, he assigned me to study a mostly cardiac condition because a very dear friend of his was suffering from ATTR amyloidosis. The same friend generously donated their heart to our research. Their heart represents the commencement of my independent professional career and launched the projects that I currently run in my laboratory. An incredible gift.

What challenges do you face in your research?

I consider myself privileged because I am surrounded by an outstanding team of students, postdocs, and scientists. My laboratory is a fantastic group of people, and I am in love with what we (or rather they) do. Every challenge that we face doesn’t feel like a struggle because of how effortlessly and collaboratively we handle them.

However, not everything is made of flowers and bunnies. My main struggle comes from balancing my personal and professional lives. I am a single mother of twins, with no family support. I am also a female migrant and a young scientist who is running a new laboratory in the middle of a pandemic. The academic jungle does not help cases like mine much. I often feel overwhelmed by deadlines, commitments, committees, hundreds of emails among many other things, as I juggle my personal challenges. And of course, I do not want to miss out on anything because that would make me less competitive for tenure. But don’t get me wrong, I love my girls and what I do, but sleep is often a luxury.

What do you hope for the future of your research?

Overall, I hope to contribute to improving the quality of life and prognosis of those affected by amyloid diseases. More specifically, I would like to contribute to the understanding of the molecular basis of ATTR amyloidosis, answering questions like how, when, where, and why does it start? And utilize this information to develop tools that can be used in the clinic.

How do you think the Alzheimer’s field will change in the next few years/decades?

The field of Alzheimer’s and other amyloid conditions is moving significantly faster than in the past. In recent years, we are seeing several new therapeutic options for Alzheimer’s and many other amyloid conditions, including ATTR amyloidosis. This advancement comes from investment, awareness, and support, and will likely continue to be fruitful. I envision the field to provide a better understanding of the causes and possible prevention strategies, and consequently, the development of efficient therapies.

What does Hispanic Heritage Month mean to you?

It means pride; I am very proud of my Hispanic heritage. I am proud of my roots and my connection to my neighbours here in America. Hispanic Heritage Month is a representation and recognition of our culture, our value, our contributions, and, why not, also our struggles. Our struggles make our contributions even more valuable, and this makes me especially proud and humble.

Are there any Hispanic scientists that you’d like to shout out?

I would like to mention Marina Ramirez Alvarado, from the Mayo Clinic (MN, USA). She is an incredible scientist, mentor, and human being. I am extremely lucky to have met her and have her as a mentor and close colleague.