Lymphoma pushes cells and tissue into an aged state

New research challenges the status quo that cancer treatments are responsible for accelerating the aging process, indicating that cancer itself also plays a role.

A team of researchers from Moffitt Cancer Center (FL, USA) has reported for the first time that lymphoma pushes T-cells and other tissues into an aged state, essentially giving patients with lymphoma the immune cells that resemble those of a much older person. This provides new insight into the combined impact of aging and cancer on the immune system and could provide new avenues to combat cancer-associated aging comorbidities.

Cancer patients often experience premature aging and the accepted wisdom was that this was predominantly caused by its treatments, such as chemo- and radiotherapy. Whilst agents of both these approaches have been shown to cause aging, there has been very little research into the impact that cancer itself has on immune cell aging.

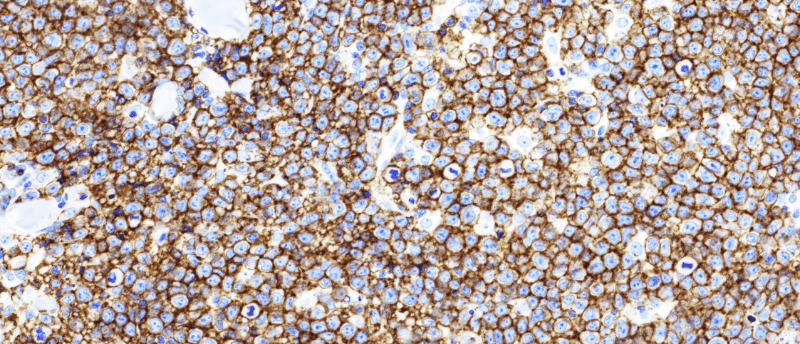

In order to investigate the role that cancer alone played in the aging of immune cells, the team utilized samples from young and aged healthy human donors and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients and mouse B lymphoma transplant models, and Eμ-Myc transgenic and mutant Myd88L252P/BCL2-driven mouse models of immature B cell lymphoma and DLBCL, respectively. They applied integrating flow cytometry, single–cell RNA sequencing, and assays for transposase–accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) in their analyses.

The study reported that B-cell lymphoma alone caused increased inflammation, impaired protein balance and altered iron regulation in T-cells, which is usually associated with older cells, as well as other tissues, including blood vessels, kidneys and intestines. It also revealed that lymphoma-exposed T-cells accumulated excess iron, making them resistant to ferroptosis. However, the aged T-cells were mostly resistant to lymphoma-induced changes, experiencing little to no variation from their already aged state.

Commenting on their findings, senior author John Cleveland stated that “Cancer doesn’t just grow in isolation; it has widespread effects on patients. We found that lymphoma alone, without treatment, is enough to provoke systemic signs of aging. This helps explain why many cancer patients experience symptoms typically associated with aging.”

Encouragingly, using a murine model the team showed that removing the tumor and any remaining lymphoma cells enabled the reversal of some of the premature aging phenotypes observed in immune cells. For instance, IFNγ production in young CD4+ T cells was restored to normal levels upon tumor clearance, while iron levels remained high and ER biomass low in some T Cells. The team hopes that this work could lead to improved health outcomes in patients with lymphoma.