Antibiotic resistance in bacteria – does history play a role?

A new study explores how bacteria evolve and adapt to sequential treatment with different antibiotics.

Bacteria possess a remarkable ability to adapt to adverse situations. Unfortunately, this translates into a major roadblock for modern medicine as multi-drug resistant bacteria evolve in response to broad-spectrum antibiotic overuse. In an effort to hinder the development of resistance, physicians often switch antibiotics in consecutive treatments. However, very little is known about how exposure to one antibiotic affects the development of resistance to drugs that are administered later. Now, Jason Papin and colleagues from the University of Virginia have answered this question with a laboratory evolution study by sequentially exposing bacteria to various combinations of antibiotics and studying their response dynamics.

“As we think about clinical problems with infection and multi-drug resistant infections, I think there’s an opportunity there to be a little more deliberate about looking at sequences of antibiotics that are used,” said Papin.

Papin’s team wondered what would happen if bacteria developed resistance to a particular antibiotic in a laboratory environment and then encountered a completely different antibiotic. Would the rate or level of resistance to the new drug change if the bacteria had a history of adapting to another drug?

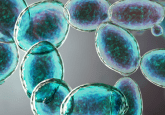

For their laboratory evolution experiments, the researchers turned to an organism notorious for its association with many hospital-acquired illnesses—the gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. They grew this bacterium in the presence of one of three different antibiotics—ciprofloxacin, piperacillin, or tobramycin—for 20 days. Following adaptation to the antibiotics, they exposed t he drug-resistant bacteria to one of the other drugs. Afterwards, Papin and his colleagues sequenced the evolved strains of bacteria to find out which mutations arose in response to the changing drug environment.

Interestingly, the scientists found several different responses to the two-drug combinations in the bacteria, depending upon the order and combination of drugs used. In certain cases, adaptation to a second drug restored sensitivity to the first drug, while in others, the rate of adaptation to the second drug was slower when the bacteria had a history of developing resistance. And sometimes, the order in which the bacteria encountered the different drugs was of paramount importance. The researchers also found a number of different mutations that arose in response to each of the antibiotics and their combinations, with both history-dependent and -independent effects occurring.

“History matters,” summarized Papin, “Evolutionary history shapes the possible future evolutionary stakes that the microbe is able to adapt towards.”

The researchers now plan to use some of their computer models to predict and understand drug order specific effects. “As we think about clinical problems with infection and multi-drug resistant infections, I think there’s an opportunity there to be a little more deliberate about looking at sequences of antibiotics that are used,” said Papin.