Old strategies may limit new Lyme disease

A newly discovered Lyme disease culprit, Borrelia mayonii, shares a transmission timeline with Borrelia burgdorferi. Will this change Lyme disease prevention tactics?

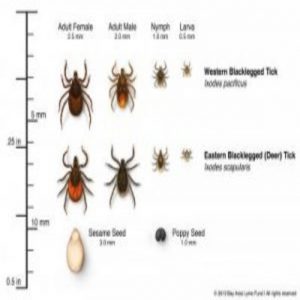

Ticks that spread Lyme are typically no larger than a sesame seed.

Credit: Bay Area Lyme Foundation

Since Lyme disease’s discovery, scientists only knew of one causative bacteria—tick-borne Borrelia burgdorferi. But, last year, researchers discovered that B. burgdorferi wasn’t the only culprit. Borrelia mayonii, also spread by ticks, led to recently confirmed Lyme disease cases in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North Dakota (1).

Now, new research from the CDC shows how both Borreliaspecies cause Lyme disease in the same window of transmission after a tick bite (2). With this new information, the researchers plan to uphold the current recommendations for prompt tick removal and use of approved repellents.

Lyme disease is the most commonly reported vector-transmitted illness in the US, affecting about 300,000 people yearly. Patients present with flu-like symptoms but can progress to widespread complications such as meningitis and facial paralysis. Cases cluster in the Northeast and Northern Midwest regions, although diagnoses also occur in other states.

Since the blacklegged tick is the primary vector for Lyme disease, most prevention methods target tick avoidance and immediate removal, especially during warmer months.

“Our research shows that the risk of becoming infected with Lyme bacteria increases with each day the tick is attached,” said senior author Lars Eisen from the CDC. “This is the basis for a key prevention message: Check yourself daily for ticks. Removing the tick within 24 hours can greatly reduce the risk of Lyme disease.”

In the new study, Eisen’s team tested the transmission rates of B. mayonii from ticks to mice at 4 time points: 24, 48, and 72 hours post-attachment, and after the tick’s full feed cycle. A nymph-stage blacklegged tick attached to a host for at least 48 hours before transmitting B. mayonii; this parallels the established attachment duration for B. burgdorferi. Transmission is rare up to 48 hours but increases to over 30% by 72 hours postattachment, the authors concluded. With this knowledge, future B. mayonii research should explore the extent of the bacterium’s geographical distribution and natural transmission factors, suggested Eisen.