How to inhibit unwanted thoughts

A key inhibitory neurotransmitter’s action in the hippocampus may explain why some people can control their thoughts better than others.

The researchers quantified neurochemistry and assessed blood flow changes to track thought inhibition (1).

Every person faces reminders that trigger unwanted thoughts, ranging from unpleasant memories and images to long-term worries. Our ability to refrain from dwelling on certain thoughts resembles stopping a physical action, according to Michael Anderson from the University of Cambridge. “We have lots of quick reflexes that are often useful but need to be controlled. There must be a similar mechanism for stopping unwanted thoughts.”

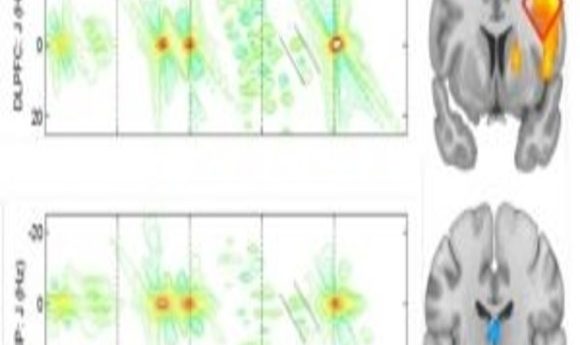

Based on prior studies, Anderson’s team knew that thought inhibition involves increased activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and diminished activity in the hippocampus, which interrupts memory retrieval and disrupts thought retention. Anderson’s team identified which brain process allows the prefrontal cortex to inhibit thought using the “Think/No-Think” procedure. In this task, volunteers learned to associate a series of words with a paired but logically unconnected word (e.g. ordeal/roach). Then, participants recalled the associated word when given a green cue or suppressed it for a red cue; in other words, when shown “ordeal” in red, they had to avoid thinking about the associated thought “roach.”

Through functional magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the researchers inspected key regions of the brain while participants tried to inhibit specific thoughts. This two-pronged strategy measured brain chemistry, not just brain activity as commonly recorded in most cognitive imaging studies.

The team found that concentrations of GABA—the brain’s main inhibitory chemical—within the hippocampus predicted participants’ abilities to block the retrieval process and prevent thoughts from returning.

“We’re surprised by how specific an answer we found after measuring GABA in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and visual cortex,” explained Anderson. “Only GABA in the hippocampus matters, which gives us a very targeted answer.”

This discovery could reconcile a longstanding question about schizophrenia and other disorders, as compromised GABA function may contribute to a failure to inhibit errant thoughts and even hallucinations.

“This elegant study of GABA spectroscopy is pretty remarkable,” commented Brendan Depue at the University of Louisville, who wasn’t involved in Anderson’s research. “Findings from studies like these, which provide basic neuroscience information, can be transformative in developing better care for individuals with ruminative, intrusive thoughts.”