What is connectomics? How microscopy and AI have combined to revolutionize neuroscience

The human brain – all 86 billion neurons of it – is something of an enigma. Despite decades of research, our understanding of how it works remains limited, presenting a major roadblock in the quest to treat neurological disease and mental illness – one that the emerging field of connectomics, recently selected as Nature’s Method of the Year for 2025, seeks to dismantle.

Connectomics strives to comprehensively map connections between synapses in an organism, in pursuit of a complete wiring diagram, or connectome, of interconnected neurons in the brain and nervous system. “Just as the genome is the set of all genes in an organism, the connectome is the set of all connections,” explained Paul Katz, Professor and Chair of Biology and Director of the Initiative on Neurosciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (MA, USA), speaking exclusively to BioTechniques.

These maps can provide detailed insights into brain structure and function, furthering our grasp of behavior, cognition and memory. In short, they have the potential to transform neuroscience.

Unfortunately, assembling a human connectome is easier said than done – current computational capacity is not up to the task of decoding our big brains – but researchers have made great strides in uncovering the intricate inner workings of the nervous systems of smaller, less complex species.

How does connectomics work?

Connectomics sits at the intersection of microscopy and AI, combining advanced imaging technologies, computational modeling and data analysis. Electron microscopy is integral to the approach, offering nanoscale resolution to allow the visualization of synapses in a way that light microscopy never could.

The first step of the process is to preserve the tissue being mapped. It must be fixed, stained and embedded, without artifacts or deterioration, before high throughput sectioning slices it into thousands of ultra-thin sections. These sections are around 1000 times thinner than the width of a human hair, each containing neuronal and cellular structures.

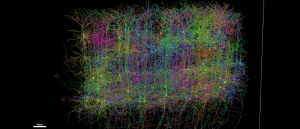

Then, an electron microscope is used to image the slices – a step that can take months. Once this is complete, the resulting images are stacked on top of each other, using computational tools to effectively stitch them together. This is followed by automated segmentation, whereby deep learning algorithms are used to segment the plasma membranes of cells from one another so that they can be traced for reconstruction and reproduced computationally in three dimensions.

Once the three-dimensional neuronal structure is resolved, individual cellular components like synapses can be identified and assigned to a neuron, eventually producing a complete connectome.

Lastly, the reconstructions must be proofread – the computational tools used are not perfect, so human oversight, which is decidedly time-consuming, is necessary.

Connectomic advances

To date, whole-animal synaptic connectomes have only been assembled for a handful of animals. The first, published back in 1986, was for the model species Caenorhabditis elegans. The seminal paper was the culmination of decades of painstaking work from the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology (Cambridge, UK), revealing the complete set of synaptic connections in the microscopic worm’s nervous system.

The computer storage required for the task far exceeded the technology of the day, and so the reconstruction had to be done by hand, finally producing a formal connectivity diagram of around 5000 chemical synapses in the organism’s 302 neurons.

It would be another 30 years before a second whole-body connectome was achieved. This time, it belonged to the larvae of the sea squirt Ciona intestinalis. In 2016, a team from Dalhousie University (Halifax, Canada) used serial-section electron microscopy to document the tiny tadpole’s entire synaptic connectome, consisting of 177 central nervous system neurons, which formed a total of 6,618 synapses.

Three years on, and the whole-animal connectomes of both C. elegans sexes were finally completed by researchers at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (NY, USA in 2019), now aided by the computer algorithms their 80s compatriots would have so dearly envied.

Then, last year, the whole-body connectome of the segmented marine annelid larva Platynereis dumerilii was announced. An international team of scientists reconstructed and annotated over 9000 neuronal and non-neuronal cells, which were classified into 202 neuronal and 92 non-neuronal cell types.

Largest brain wiring diagram generated from grain-sized sample

Inside the most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date.

While whole-animal connectomics hasn’t been carried out in larger species, scientists have had some success mapping just the brains of more complex organisms. In 2024, an international cohort of researchers called the FlyWire consortium reported the full connectome of an adult Drosophila melanogaster brain. They created a neuronal wiring diagram of the whole brain of an adult female fruit fly, containing 50 million chemical synapses between 139,255 neurons.

In mammals, we’re a long way from plotting entire connectomes, but some inroads have been made in delineating portions of the brain. In 2024, for example, researchers reconstructed 1 mm3 of human temporal cortex. Then, last year, scientists published a collection of ten studies describing the largest wiring diagram and functional map of a mammalian brain to date.

Firstly, a team from Baylor College of Medicine (TX, USA) and Stanford University (CA, USA) recorded brain activity from 1 mm3 of a mouse’s visual cortex as the animal watched various video clips. Next, Allen Institute (WA, USA) researchers took that same slice of the brain and divided it into more than 25,000 layers before using an array of electron microscopes to take high-resolution images of each slice. Lastly, a team at Princeton University (NJ, USA) used AI to reconstruct the cells and connect them into a 3D volume, containing over 200,000 cells and 523 million synapses.

The future of connectomics

Such breakthroughs have already reshaped what we know about the brain – and this is just the tip of the iceberg. Take the Drosophila connectome, for example.

“It has revolutionized research on Drosophila,” Katz told BioTechniques. “Because there are also tools to allow targeting of trans genes to specific neurons, you can now work out how neural circuits function at a scale that was not feasible before. Previously, it was a cell-by-cell process to find the connections between neurons. Now, it’s an exploration of a map that has all of the connections.”

If we can replicate these findings in other animals, who knows what we might uncover? Access to whole-body or whole-brain connectomes for more species may shed light on how nervous systems function and provide insight into the evolution of neural circuits and behavior.

Technological advances could help usher this dream into reality – in fact, they’re already doing just that, Katz explained.

“Advances in machine learning and imaging technology are making it so that creating a connectome is not just for the large institutes like Janelia [VA, USA] and Allen,” he noted, adding that this increased multiplicity of institutions should foster more innovation.

“I think that we’ll see a broader diversity of non-model species with connectomes. For example, my lab is working on the connectome for a nudibranch mollusc,” Katz continued.

One technology that will be particularly useful is comparative connectomics. For example, by comparing individual connectomes, scientists can understand how behavioral differences align with neural circuitry, and by studying interspecies connectomes, they can get a glimpse into what features are conserved in different animal brains.

“The field of comparative connectomics will allow us to determine what the general principles are. If all work were focused on two species, then we would not know if the synaptic organization that they have is peculiar to them. It is only by making comparisons that we can find general principles and evolutionary novelties.”

Despite his optimism on this aspect of connectomics, scaling up to map larger brains is still a distinct challenge. We asked Katz whether we’ll ever get a complete human connectome – his response: “I’m really bad at predicting the future. In order for there to ever be a human brain map, we would need continued and steady support for scientific research. If NIH [National Institutes of Health (MD, USA)] and NSF [National Science Foundation (VA, USA)] are not reliably funded, then they can’t make long-range commitments to moon-shot projects like a human brain connectome.”

It seems the future of connectomics is as much a political question as a scientific one. It’s anyone’s guess what the coming years will bring for the field, but one thing’s for certain: if we can continue to map the intricate networks of connections within the brains and nervous systems of an array of organisms, we stand to transform our understanding of brain function and dysfunction, potentially paving the way for novel neurological therapeutics.