It’s time to give small proteins a bit of the limelight

Aisha Burton is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the National Institutes of Health (NIH; MD, USA), where her research focuses on characterizing small proteins to understand regulatory mechanisms, including how small proteins help Escherichia coli (E. coli) regulate its stress response. Here, our Assistant Editor, Aisha Al-Janabi, speaks to Aisha about her research, the challenges of studying small proteins and the advice she would give to her younger self!

Aisha Burton is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the National Institutes of Health (NIH; MD, USA), where her research focuses on characterizing small proteins to understand regulatory mechanisms, including how small proteins help Escherichia coli (E. coli) regulate its stress response. Here, our Assistant Editor, Aisha Al-Janabi, speaks to Aisha about her research, the challenges of studying small proteins and the advice she would give to her younger self!

What techniques do you use to study small protein modulation of E. coli activity?

You need a couple of different techniques to study this but for the majority of my work, I use molecular genetics techniques and biochemistry. I perform a lot of PCR to amplify DNA fragments and we use tags on the end of a protein to increase its size or see it. I run western blots to detect a specific protein, and sometimes northern blots to look at the RNA.

How can small proteins change the activity of E. coli?

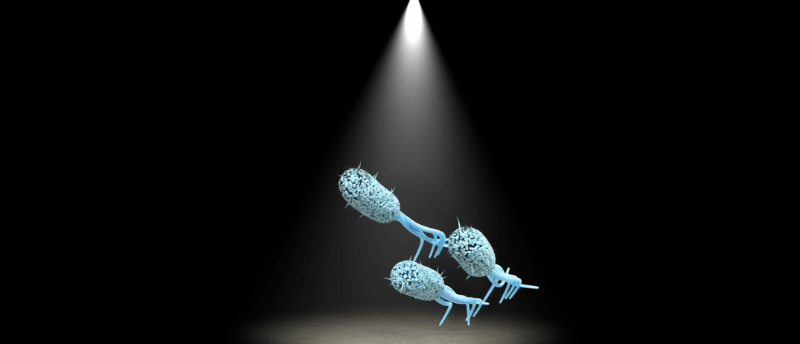

To date, there are several small proteins that have been studied in E. coli. One protein that is cool works with a two-component system, containing two proteins called PhoQ and PhoP. PhoQ sits in the membrane and senses what’s going on, and PhoP is a transcription factor, which can tell the cell to turn on in certain genes. Two small proteins have been identified for this system, MgrB and SafA, which turn the system off and on respectively.

This is of interest because a lot of pathogens, for example, E. coli or even Salmonella, utilize this two-component system to increase their virulence. It has been suggested that MgrB could be used as a therapeutic in the future to turn this system off, making the bacterium less pathogenic.

What type of impact do you think this research could have?

Small proteins are 50 amino acids or less and traditional research has focused on looking at much larger proteins. Recently, we’ve found that these small proteins are present in eukaryotes, archaea and prokaryotes, they are in all domains of life. One of these small proteins found in eukaryotes has been implicated in muscular dystrophy where it has been found to be dysregulated.

We don’t actually know how many small proteins there are and so studying these small proteins in prokaryotes could help to inform us about the number of small proteins present in eukaryotes. I believe the literature suggests there are about 5000 small proteins in eukaryotes, but they haven’t been well studied. This is a new area of study for someone to get into if they are interested in this type of research.

Why do you think there have been limited studies about small proteins?

They are hard to work with. Take, for example, the western blot. You need to run a gel and sometimes those small proteins are so small they run off the gel. You wouldn’t even know that you missed something if you didn’t think to look for them.

A lot of the bioinformatic techniques previously used computer learning, which thought of the small proteins as noise and focused more on the bigger products. But now, people have started to take a second look at this information and see what they might have missed. There are some labs, including the lab I am currently working in, that have done a re-annotation of the E. coli genome to see what has been missed.

We also use a protocol called ribosome profiling with drugs to pause translation to see which small proteins we might have missed. This protocol allows you to see where ribosomes reside within a cell, which will tell you where translation is starting. This suggests where active protein production is occurring in the cell.

What are you most proud of in your career?

I am most proud of getting my PhD. I switched labs, which a lot of people think is taboo and you shouldn’t do, but I needed to. I didn’t feel like I was getting the mentorship that I needed. After 3 years in the lab, I needed to change and I switched after candidacy. I still graduated on time with my peers, which was really awesome.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

That’s a great question. I always struggled with this question, because there is so much that I want to tell little Aisha growing up.

You need to have a community and I would tell my younger self to start building a community earlier. When I say community, I mean people who advocate for you and people who support your dreams. I don’t think I would be where I am today without my community. I lean on my grad school friends to this day. I am in the fourth year of my post doc and I am still chatting with those ladies that I studied with for my qualifying exams. We’ve stayed friends to this day!

I would also tell myself to take a break. It is okay to rest; you don’t have to keep grinding. I did not take a break between my PhD and my post doc, and I should have taken a few months to rest. You don’t always have to keep going and going and going. I always joke: if I die today my boss would get a new post doc tomorrow. Grim, right? But it is true. You have to take care of yourself, you have to rest and you have to make yourself a priority.

I always tell people take time, take your vacation, don’t be shy to say no and just do your self-care.

Lastly, go and talk to a therapist. I don’t think taking care of your mental health is talked about enough in science. You keep grinding, but at some point, you need to talk to someone. It is not healthy to always keep working harder and harder. A lot of people experience anxiety and depression and don’t speak about it. But there are therapists in place, sometimes insurance will pay for it, and many colleges and universities do provide at least one or two sessions for free.

That’s great advice, I think we all need to be reminded to rest more. What resources or networks have you found particularly useful in your career?

I always encourage people to go to scientific conferences, if you can, where you can network with people. I met my postdoctoral PI, the person I am working for now, at a conference. She heard my talk and was really interested in having me come work for her. If I didn’t give a talk at that conference, I may not be where I am at today. Some of the larger conferences may not be as trainee friendly because you have 100s of people attending and you don’t know who to talk to, but I’d still encourage you to go, especially if you are giving a poster or a talk. You never know who you might meet!

Science Twitter is also a really good place to meet other people in your field who are doing similar things. When I say science Twitter, I mean a Twitter account you use for your work in science and use to follow and engage with other scientists. Sometimes you go there for advice or try to see what the latest scandal is. People post jobs, and people ask how to negotiate for a job. You always get some mix of things. There is a wealth of knowledge on science Twitter.

One useful hashtag is #WomeninSTEM, and #BlackinSTEM is great to find others like Black or African American scientists. There are also discipline-specific ones, like #BlackinMicro, which I use a lot as a microbiologist.

When I was in graduate school, I only knew about one other Black woman microbiologist, I knew several men, but I didn’t know any other Black women microbiologists. From the Twitter movement, I was able to find more, and I was like, “Oh man, there’s more!”. There are more people like me, and so that exposure on Twitter helped me find this other community that I can lean on. That was really cool.

Closing thoughts

I am thankful for the opportunity to share my voice. I think we need to hear from more women in science and just women in STEM because we are still a minority. I think it is getting better. I feel like we are at the cusp of getting better in the field. I am super hopeful that there is momentum moving forward.

I am thankful for the opportunity to share my voice. I think we need to hear from more women in science and just women in STEM because we are still a minority. I think it is getting better. I feel like we are at the cusp of getting better in the field. I am super hopeful that there is momentum moving forward.

Girls rock. Like Beyoncé says, “Who runs the world? Girls”