The Color of North: communicating protein science through art and narrative

To biochemists, there’s nothing more interesting than a protein. But explaining the fascinating intricacies of proteins to people who aren’t scientists can be challenging. That’s why biochemists Shahir Rizk and Maggie Fink decided to write a pop science book about the unsung heroes of molecular biology: proteins. Through creative storytelling and artistic illustrations, Shahir and Maggie take readers on a journey, from antifreeze proteins that allow organisms to survive in extreme cold to the remarkable cryptochromes that give migratory birds their own perception of ‘north’.

Here, Shahir and Maggie discuss their motivation for the book, The Color of North, the differences and similarities between creative and academic writing, and how they honed their storytelling skills. They have also provided us with an excerpt from the book, which you can find at the bottom of the page.

What inspired you to write this book?

Both of us were interested in finding a way to make our research and proteins in general more accessible to non-scientists. We also had both read a lot of pop science books, most of which focus on nature, animals and trees. The books that do talk about topics at the molecular level focus on DNA, genes and disease; proteins were nowhere in the conversation.

Aside from being motivated by our love for proteins, we were inspired by other incredible science writers, primarily Robin Wall Kimmerer. We both read her book, Braiding Sweetgrass, and knew that not only did we want to write about proteins, we wanted to tell stories and write outside the box of traditional science writing.

How did the two of you come to collaborate?

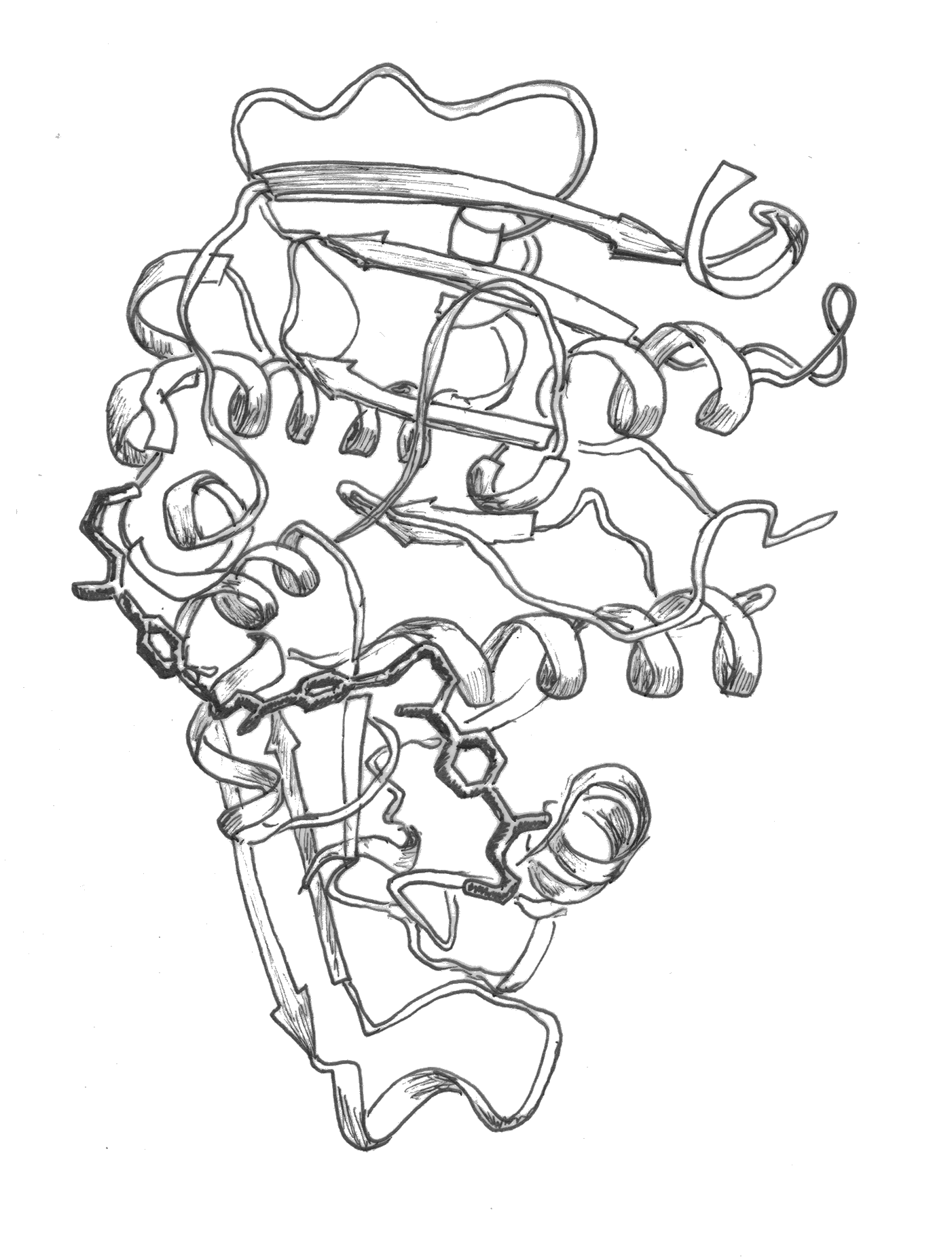

Illustration of an engineered protein that can digest PET, the main component in many plastic products. Credit: The Color North.

Our work has always been collaborative. Prior to writing this book, we had been working on some research projects together for a few years, so we knew each other well and thought similarly about not only how we approached science questions but also our creative processes. Shahir initially told me he wanted to write a book about proteins and asked me to read some of his writing and give him feedback. Around that time, I was taking a creative writing course that focused on graphic novels and memoirs. I began painting various protein structures and writing about them for my non-scientist classmates. I brought them to Shahir for his input, and from there we decided that we should not only write the book together, but also incorporate art with the illustrations of protein structures.

How did you find writing the book compared to a research paper?

There were many similarities – lots of research and reading. Just because we’re biochemists doesn’t mean we know everything about proteins, so we read a lot of scientific literature for every chapter. In that sense, the experience was similar to writing a research paper. However, there is a lot more freedom to craft the narrative in a book like this. We could push the boundaries of how we talked about complex ideas. Writing The Color of North was more of a creative exercise to accurately represent the science while telling compelling stories.

The book also went through the peer review process, like a research article would. We had to address reviewer comments, make changes and go through several cycles of edits. We pushed back and insisted on keeping certain things because we believed they were important both creatively and scientifically. The peer review process is not always fun, but it is critical for science. However, for the book, we had to navigate where precision and technicalities needed to be prioritized and where accessibility and storytelling were more important for the reader’s experience.

What challenges did this represent?

One of the biggest challenges was figuring out how to explain science without jargon. As scientists, we often take for granted how much we assume someone might know about our field of expertise. But that challenge gave us space to play and push ourselves to be better communicators, writers and even scientists.

A specific example of this was brought up by the peer reviews when we first introduced proteins. In a biochemistry class, the first thing you learn about proteins is that they are made of amino acids and they have primary, secondary, tertiary structure, etc. But in the book, we don’t introduce any of that until halfway through because we didn’t want the reader bogged down with jargon. So, how do you explain proteins and their shapes without the language we use as scientists? That was a challenge, but a fun one.

How did you hone this style of writing?

Reading. Lots of reading. We have always been avid readers and read many different genres and styles. At the time of writing the book, we were both reading a lot of poetry and actively avoiding reading any pop science books. Exposing yourself to good writing, and even bad writing sometimes, can help you figure out your voice and give a starting point for experimenting with your writing. The same is true for scientific writing. The more you read, the better a writer you will become.

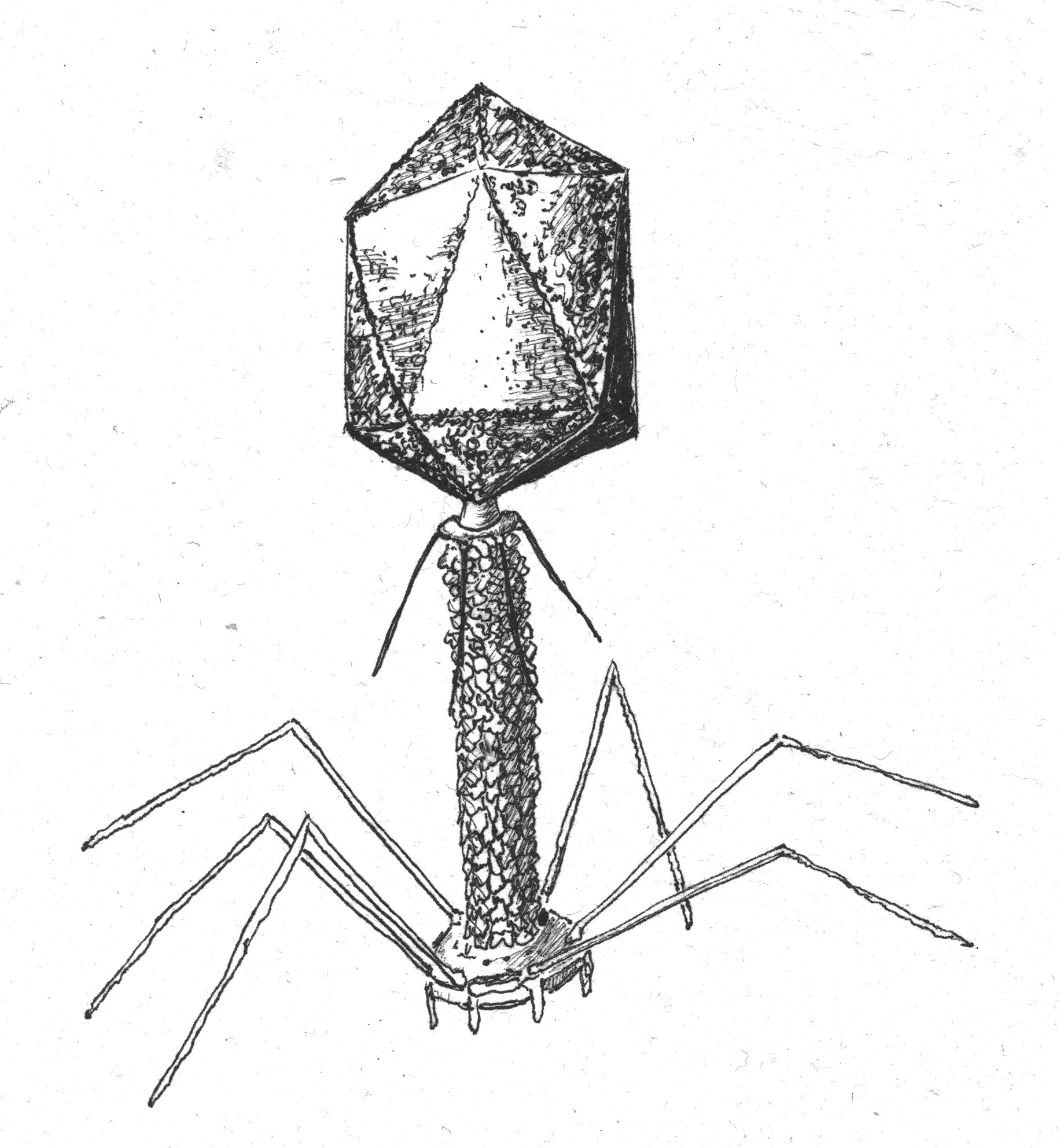

Illustration of a bacteriophage. Credit: The Color of North.

We were also writing a lot before working on this book. We would journal and write poetry or stories. We would share some of it with people, but mostly it was just for ourselves. Writing in any style takes practice, and we had been practicing a lot before writing the book. Even now, we have to remember that most of what we write will either be terrible or need a lot of work to make it readable. But you can’t get better at anything without practice. And through that process, you can figure out your voice and just have fun with words and language in a way that we don’t always get to do as scientists.

Did you discover anything particularly surprising in your research for the book?

Even though the two of us have studied proteins for years, the more we looked, the more we found new and ever more fascinating examples of how proteins help organisms survive. Antifreeze proteins were a particularly surprising discovery for us; it was mind-blowing to know that plants, insects and even bacteria use proteins to stop frost from damaging their cells, allowing them to grow in very cold climates. What’s even more mind-blowing is how some frogs use a class of proteins known as nucleating proteins to protect themselves from the cold. With these proteins, the frogs can survive being frozen solid without damage to their tissues. When a spring thaw comes along, the frogs come back to life.

Where does the title, ‘The Color of North’, come from?

This was another fascinating example of how proteins give some animals truly superhuman abilities. There is a class of proteins known as cryptochromes found in most organisms, including bacteria, plants, animals and humans. These proteins are light receptors – we use them to regulate our circadian cycle. In bacteria, cryptochromes are used to defend against UV light damage, and plants use them to track the arrival of spring and to grow towards a light source. But in some migratory birds, cryptochromes take on a truly fascinating function that seems more like science fiction. By receiving light, the bird cryptochromes can align a single unpaired electron with the magnetic field of the Earth. The protein then sends a signal to the brain through the optic nerve, giving the bird a color that it calls ‘North’, a color that we can’t see or perceive but can only imagine.

What excerpt have you shared with us and why did you choose it?

We chose a section from the last chapter of our book. The chapter title is ‘Resurrection’, referring to how protein engineering is ushering a new revolution in biotechnology that promises to tackle some of the world’s most challenging problems. The section focuses on how different computational algorithms and AI are reshaping how we look at protein structures and how we can design new ones. This new wave of engineered proteins is slated to help develop new therapies and innovative solutions to pollution and climate change.

What is one thing you would like your readers and fellow researchers to take away from the book?

Of course, we hope any reader takes away an appreciation for biochemistry and proteins. That is a huge part of why we wrote the book. But now, on the other side of this process, we would love for the reader to walk away curious and empowered. Curious about how connected we are to the world around us and empowered to become seekers. We also hope to encourage more scientists to write and to engage with the public in more accessible ways.

The Color of North is available to buy here.

Meet the authors

Shahir Rizk (left) is an Associate Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Indiana University South Bend and the Indiana University School of Medicine (both IN, USA), whose work focuses on protein engineering with applications in biosensor design.

Shahir Rizk (left) is an Associate Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Indiana University South Bend and the Indiana University School of Medicine (both IN, USA), whose work focuses on protein engineering with applications in biosensor design.

Maggie Fink (left) is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Notre Dame (IN, USA). Her current research focuses on the genetic and molecular mechanisms of virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In addition to her research position, Maggie is the science communication postdoc in the College of Science at Notre Dame, where she focuses on community outreach and engagement as well as training other researchers to be better science communicators.

Maggie Fink (left) is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Notre Dame (IN, USA). Her current research focuses on the genetic and molecular mechanisms of virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In addition to her research position, Maggie is the science communication postdoc in the College of Science at Notre Dame, where she focuses on community outreach and engagement as well as training other researchers to be better science communicators.

Book excerpt

Below is an excerpt from Chapter 10, called Resurrection.

Chapter 10_ Pages from Rizk-Fink_txt_final-watermarked

The opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of BioTechniques or Taylor & Francis Group.