A modern-day Frankenstein’s monster?

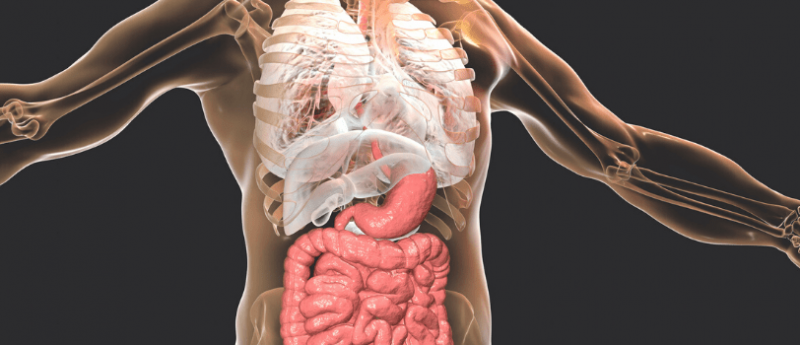

Lab-grown model of the human body comprised of an integrated body-on-a-chip multi-organoid system could pave the way for quicker pharmaceutical testing.

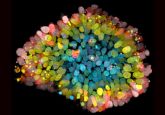

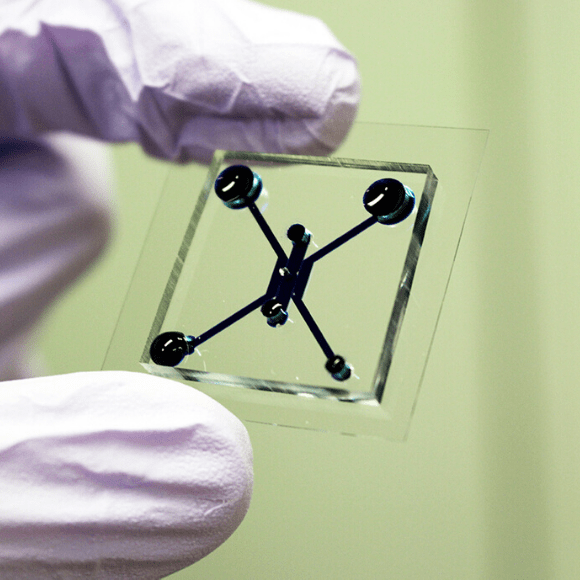

New research published in Biofabrication this week describes the creation of the most advanced lab model of the human body to date. The body-on-a-chip is comprised of primary cells and stem cells and contains many of the cell types that are present in human tissues. Modeled organs include the lungs, liver and heart, each approximately one-millionth the size of its full-sized counterpart.

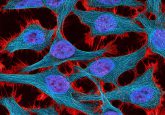

Created by scientists at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM, NC, USA), the organoids were made by isolating individual organ cell types and engineering them into miniature versions of the required organs. Each organ contains nearly all the cell types that it would be comprised of in the human body, including, immune cells, blood vessel cells and fibroblasts.

With the eerie concept of a lab-created human body, it’s easy to see the comparisons with Frankenstein’s enigmatic monster. However, with less tragic subtext and fewer angry villagers, it is hoped the multi-organoid body-on-a-chip system can provide a physiologically accurate system for drug screening.

The body-on-a-chip system has already been proven to be effective for the screening of drug toxicity, even with drugs that had previously been shown as safe in standard 2D cell culture and animal models. Some adverse effects of these drugs were not demonstrated in three rounds of human trials.

“The most important capability of the human organ tissue system is the ability to determine whether or not a drug is toxic to humans very early in development, and its potential use in personalized medicine,” explained the study’s senior author Anthony Atala. “Weeding out problematic drugs early in the development or therapy process can literally save billions of dollars and potentially save lives.”

New tumor-on-a-chip could pave the way for the discovery of cancer drugs

New tumor-on-a-chip could pave the way for the discovery of cancer drugs

New tumor-on-a-chip device enables researchers to mimic tumor conditions, allowing for greater accuracy when screening new cancer drugs.

A key component of this system is the microfluidic circuit, which functions as the blood circulatory system, cycling a nutrient and oxygen-containing medium throughout the organs. This circuit allows accurate modeling of drug effect, allowing true-to-life dissemination of a drug, as well as the removal of the products produced when a drug is metabolized.

Scientists at WFIRM have spent nearly 30 years developing lab-grown human organs for patient transplants, and to date, clinical trials have been conducted in humans for more than 15 tissue and organ types.

“Creating microscopic human organs for drug testing was a logical extension of the work we have accomplished in building human-scale organs,” commented study author Thomas Shupe.

Shupe continued: “Many of the same technologies we have developed at the human-scale level, like including a very natural environment for the cells to live in, also produced excellent results when brought down to the microscopic level.”

It is hoped that this Frankensteinian model can significantly impact pharmaceutical screening processes by expediting drug testing, decreasing clinical trial costs and reducing the reliance on animal models.