Improving CAR T-cell therapy for cancer treatments

New strategies developed to boost response to CAR T-cell therapy and reduce its toxic side effects.

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic (MN, USA) have developed new methods in the hope of improving the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-T cell) therapy for the treatment of cancer.

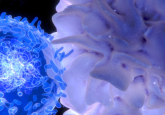

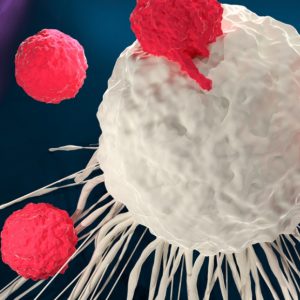

“In CAR T-cell therapy, physicians remove and modify a patient’s T cells to recognize and fight cancer,” explained Reona Sakemura a researcher in the lab. “Once modified T cells are reinfused into the patient where they seek out and ultimately kill cancer cells.”

Though proven successful as treatment for certain cancers, it has toxicities that limit its widespread application. Such toxicities include neurotoxicity and cytokine release syndrome, in which patients can experience fever, nausea, headache, rash, tachycardia, hypotension and difficulty breathing. CAR T-cell therapy patients often get sick during treatment and some cases of death related to the side effects have been reported.

The newly developed strategy involves blocking the CAR-T cell produced protein GM-CSP using the antibody lenzilumab. “When we blocked the GM-CSF protein, we found that we could reduce toxicities in preclinical models,” commented Rosalie Sterner, lead author of the paper. “We also were able to demonstrate that CAR-T cells worked better after the GM-CSF protein was blocked”.

The research then used the gene editing technique CRISPR to prevent the cells from producing the protein in the first place. The modified cells were also shown to be more effective than regular CAR-T cells.

Based on the results, the research is moving into a Phase II clinical trial to test the efficacy of the GM-CSF blocking antibody when it is used alongside CAR T-cell therapy.

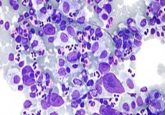

The results for CAR T-cell therapy vary based on the type of cancer being treated; B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia has a 90% response rate whereas rates for other blood cancers remain low. To improve its effectiveness in other cancers, the team developed a method that combines the therapy with a drug called TP-0903. The drug targets the AXL protein, something found on cancer cells and in the cancer environment. It has also demonstrated an ability to increase the efficacy of the CAR T-cells in attacking cancer cells and may lower the treatments toxic side effects.

Further trials are needed for both methods though the team hope for these new strategies to become standard when delivering CAR T-cell therapy. Sakemura added “We believe the latter effect may eventually be utilized as an innovative approach to augment the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy and extend its use to other B cell cancers”.