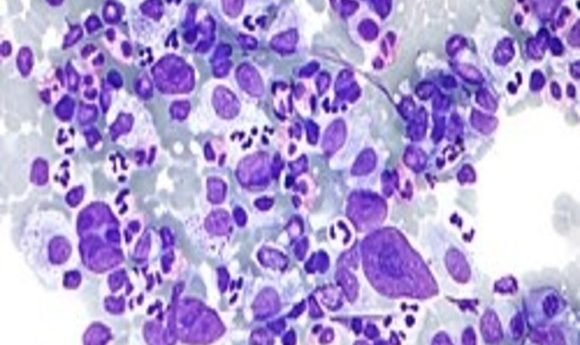

What’s old is new again in a novel anticancer strategy

By altering cancer cells, researchers make them vulnerable to existing treatments.

Micrograph showing Hodgkin lymphoma.

Credit: Wikipedia

Monoclonal antibodies presented a major step forward in treating cancer. Drugs such as rituximab lock on to surface proteins distinctly produced by neoplastic cells and deliver death via apoptosis. Some newer therapies recruit the patient’s own immune system to do the killing by inhibiting the cancer cell’s ability to evade immunosurveillance or by reactivating agents within the immune system that malignant cells have rendered impotent or blind. But cancer is a wily adversary, and certain forms of the disease, Hodgkin’s lymphoma for example, have continued to evade even these latest advances in immunotherapy. That is, until now.

In a recent study published in the journal Blood, Jing Du and his colleagues describe a strategy that appears to work around the immune-evading tactics of classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) cell lines.

Existing research shows that classic Hodgkin’s cells are mutated B-cells that display no phenotypical markers distinct to the B-cell line. Du and his team hypothesized that, because antibody therapies have proven effective against B-cell Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a restoration of B-cell phenotypic properties such as CD20 cell-surface markers may render cHL cell lines vulnerable to attack using extant antibody therapies.

The team cloned a complete complementary human bcl2 gene into a retroviral murine stem cell virus and employed plasmids possessing B-cell-specific promoter sequences. They infected cHL and B-NHL cell lines with the virus after transduction with the plasmids. Then the researchers performed a pharmacological screen using cHL cell lines carrying a CD19 reporter and identified three compounds that promoted re-expression of the B-cell phenotype.

Du’s team discovered that combining either all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) or arsenic trioxide (ATO) with one of the screened pharmacological compounds produced a re-expression of CD20 in cHL cell lines. Once the expression of CD20 was restored, the malignant cells became susceptible to attack by existing antibody therapies.

I thought it was pretty elegant work,” said Paul Hamlin, an oncologist and clinical investigator at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Hamlin was not a member of the research team. “They actually showed they could reactivate genetically silent B-cell characteristics in the lab with agents we know cause differentiations: ATRA and arsenic trioxide.”

While an exciting advance, the work is far from ready for the clinical setting. Most cell lines arising from classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma in patients tend to involve infection with the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV). Hamlin describes the characteristics of EBV-infected cHL cells as differing widely among patients according to age. Du and his colleagues did not clarify whether they restricted their cell lines to EBV-driven cHL, so the applicability of their work may be somewhat limited, according to Hamlin.

“It would be better if [the cell lines] were EBV-positive,” said Hamlin.

Nevertheless, the study is promising, especially in its use of existing therapeutic agents.

“What I thought novel and exciting was ATRA and ASO are readily available,” said Hamlin. “They’re already approved.”