It’s okay to turn to your neighbor for help – but maybe not for AML cells

A vicious interaction between two cells causes rapid growth of the deadliest leukemia, but the good news is researchers have identified the molecules driving it and are testing a drug to stop it.

A study published in Cancer Discovery found a link between neighboring cells in the bone marrow that may lead to an exciting new treatment option for the deadliest blood cancer. The team, led by Marta Galán-Díez from Columbia University (NY, USA), found this fascinating interaction between leukemia cells and osteoblasts that creates a cycle driving Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) progression.

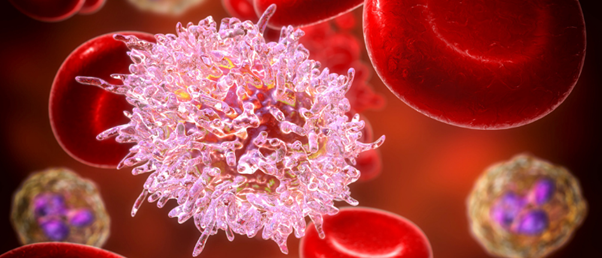

AML develops in either myeloid stem cells or myeloid blasts, which differentiate into white blood cells. With patients already suffering from a reduced immune system, treatment is limited to chemotherapy. The intensity of which depends on the patient’s ability to handle the chemo, putting some patients in a highly vulnerable position. While remission is possible, the disease often re-emerges resistant to treatment when the stem cells evolve to evade treatment. This makes drug development particularly challenging.

The study in question investigated the interaction mechanism between the two different cell types and how to harness this knowledge to move towards better treatments. Leukemic stem cells release kynurenine, a molecule that binds to the serotonin receptor presented by osteoblasts. This promotes the production of an acute-phase response protein, SAA1, which in turn, encourages the production of kynurenine in the leukemic stem cells, creating a vicious cycle that acts as a driver of cancer growth.

Steal to survive: pancreatic cancer’s secret to tumor growth

Steal to survive: pancreatic cancer’s secret to tumor growth

Using optical metabolic imaging, researchers find pancreatic cancer cells hijack metabolic activity from non-cancer cells to boost proliferation.

Researchers found if they can block this cycle, they can stop progression of the disease. “The advantage of this approach is that it doesn’t matter which stem cells are causing the disease. They all need osteoblasts to grow, and if we can stop these two cells from communicating, we might be able to stop the disease,” commented Kousteni.

In the first phase of the study, researchers genetically removed the serotonin receptor on the osteoblasts in mice, which successfully stopped progression – proving that without this communication pathway, the disease slows. The study then tested a drug called epacadostat, which is being tested for other cancers, that inhibits kynurenine synthesis. When used in conjunction with chemotherapy, epacadostat substantially affected AML growth.

To confirm the findings from the mouse models are applicable in humans, the team of researchers monitored patients with AML and observed increasing levels of both the critical communication molecules – kynurenine and SAA1. They also looked at patients with myelodysplastic syndrome – another cancer that often develops into AML – and found that with the progression from one cancer to the other, levels of kynurenine and SAA1 increased.

The results from this study provide hope that with a better understanding of one of the key mechanisms driving the rapid growth of this cancer, we might be able to block the nurturing environment osteoblasts currently provide. It’s safe to say that in this instance it might be better for these cells to cut contact and go elsewhere for neighborly support.