Viruses join the fight against cancer

Engineered viruses may become our unlikely allies in preventing intestinal cancers.

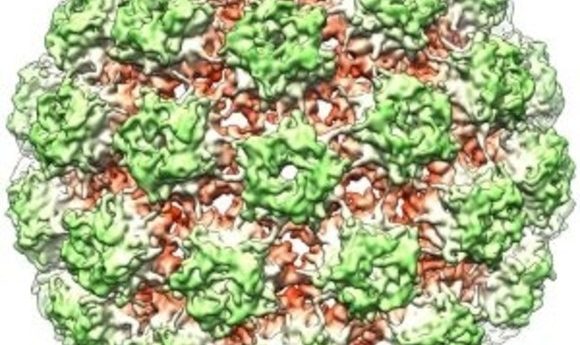

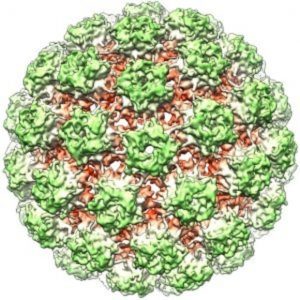

The 3D structure of the bovine papillomavirus (BPV) capsid.

Credit: Wikimedia

In 1891, the American surgeon William Coley took the unusual step of injecting cancer patients with bacteria in the hope of provoking a strong immune response that would help eradicate tumors. Today, he is known as the father of cancer immunotherapy.

Now, a new study by Liang Qiao and colleagues at Loyola University in Chicago explores whether viruses might also promote an anti-cancer immune response. The team used papillomaviruses—the same viruses notorious for causing cervical and skin cancers—to induce immunity against developing intestinal cancers.

“We discovered that the pseudoviruses—basically, the papillomavirus shell with plasmid inside—when they are orally given, can induce tumor regression in the intestinal tumor model,” said Qiao.

Cancer cells evade immune pathways in devious ways, suppressing local immune responses and escaping identification by patrolling macrophages. One of the most promising approaches for fighting cancer, immunotherapy focuses on training the immune system to recognize and attack these elusive tumor cells.

Traditional immunotherapy depends almost exclusively on the adaptive immune response—the function of the immune system that is specific and retains long-term immunological memories. Adaptive immunity consists of the cytotoxic T-cell response and antibody-based humoral immunity, and it is distinct from innate immunity, which is the body’s first level of defense against invading pathogens.

In the new study, Qiao and colleagues used papillomavirus pseudoviruses consisting of the outer protein shell of a papillomavirus surrounding a DNA plasmid bearing a cancer-cell specific antigen. The researchers orally immunized a mouse model of the early stages of colon cancer featuring spontaneous development of numerous benign intestinal tumors that sometimes proceed to form adenocarcinomas. They discovered that most of the tumors regressed within a short period of time. This was accompanied by a robust induction of both cellular and humoral immunity, and the lifespan of these mice nearly tripled.

The viruses used by Qiao’s team have two major advantages when it comes to targeting intestinal cancers. Intestinal tumors form on the mucosa, which is a specialized membrane that lines the gut. Since papillomaviruses normally infect mucosal membranes, they can specifically target the intestinal mucosa when given orally and induce immune response in these cells. Secondly, the viral protein shells allow them to survive the harsh acidic conditions of the stomach and small intestine, letting them safely reach their site of action.

Surprisingly, a pseudovirus containing just a control plasmid or even just the viral shell with no DNA inside was also sufficient to reduce tumors and increase lifespan. This led the researchers to hypothesize that non-specific innate immune pathways and not the adaptive immune response were responsible for tumor eradication.

Upon further investigation, this was indeed proven to be the case. On reaching the intestinal mucosa, the pseudoviruses activated inflammasomes, multimolecular complexes that aid innate immunity. The inflammasomes induced a form of programmed cell death in the tumor cells, leading to tumor regression.

The adaptive immune response, however, seemed to serve a different purpose. While not appearing to participate in the initial tumor regression, adaptive immune responses were crucial for maintaining long-term immunity against tumors and preventing tumor relapse.

“This is, I think, the first report on using or targeting inflammasomes or innate immunity to treat cancers,” said Qiao, who hopes that the results of this study will translate into clinical research in the near future.

“I think [this study] has real impact because it’s targeting a disease, colorectal cancer, that has not really proven to be immunogenic,” said Sharon Evans from Roswell Park Cancer Institute, who was not involved with this study. “The idea that you could use another type of innate immune response activating agent to prompt or provoke the immune response is really intriguing.”