Growing replacement organs in animals

New techniques enable researchers to grow organs from stem cells in a host animal.

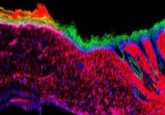

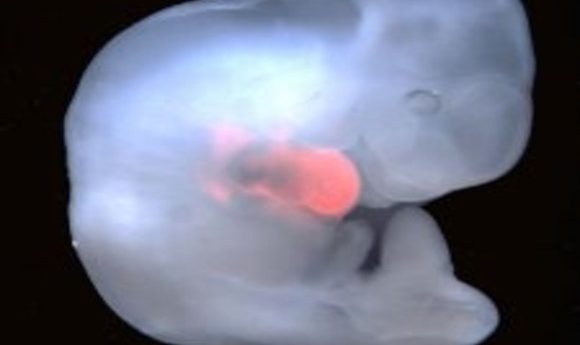

Cells derived from rat pluripotent stem cells (in red) were enriched in the developing heart of a genetically modified mouse embryo.

Credit: Jun Wu and Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte

Organs such as the pancreas, heart, and eyes can be derived from rat stem cells and then grown in a mouse host, a new study in the journal Cell shows. These findings shed light on the biological cues that control the normal development of these organs and also advance a goal of regenerative medicine: regenerating organs for transplantation.

“This study provides several examples that we can recreate the environment that allows stem cells to grow into an organ inside another animal,” said Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte from the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, senior author of the paper.

For many years, researchers have tried to grow human organs from stem cells in vitro by supplying growth factors known to be important. But those attempts were largely unsuccessful because the number and timing of cues for normal development remain incompletely understood.

Belmonte and his team took a different tack. They decided to exploit the environment inside a host animal, which already produces the necessary cues for normal development of these organs, explained Jun Wu, a staff scientist in Belmonte’s lab and first author of the study.

The researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing techniques to knock out a gene necessary for pancreas development in the mouse. They then generated rat stem cells and introduced them into the modified mouse embryos very early in development. The mice were unable to produce a pancreas, but the rat stem cells followed developmental cues in the mouse body and developed into a functional pancreas. These mice survived beyond a year, suggesting that the pancreas grown from rat cells was completely functional.

The researchers performed similar experiments knocking down genes necessary for heart and eye development in the mouse. In both cases, rat stem cells developed into the missing organs.

To explore the possibility for creating human organs in animals, the researchers introduced human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells into a pig host. Some of the human iPS cells integrated into the pig host, but many were lost. In the future, the team plans to use CRISPR gene editing in pig hosts to see if functioning human organs can be grown from iPS cells.

The study opens up new avenues for investigating the basic rules of development. The development of human organs and tissues could be studied in a host in vivo, where the micro-environment is more natural than in a culture dish, said Wu. These models could also be used to understand human genetic diseases; using human stem cells derived from a patient, it may be possible to examine how the disease is initiated from early embryonic stages. Finally, the chimeric animals might provide a better model for testing drug toxicity and efficacy directly on human tissue in chimeras, explained Wu.