How to use berries for medicine

Health gurus may tout the power of berries to treat disease, but why are they considered therapeutic? Cyanidin, a small molecule in berries, might provide the answer.

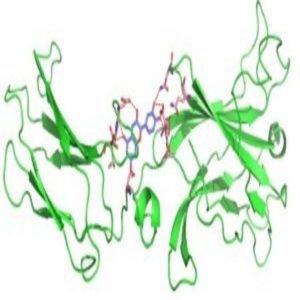

Cyanidin prevents IL-17A from binding by blocking IL-17RA.

Image courtesy of Qin Jun and Liang Zhu.

Berries are not only delicious, but they also reduce inflammation associated with diseases such as asthma, diabetes, and cancer. The anti-inflammatory property of berries comes from flavonoids, small molecules present in berries and other plants. Now, a recent article in Science Signaling identifies the flavonoid cyanidin as an inhibitor of interleukin 17A (IL-17A), a signaling molecule that contributes to inflammation and disease (1).

“Il-17 is a well-known target and has been well established as a target for several diseases,” said Jun Qin, from the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute, co-corresponding author of the study. After studying IL-17A signaling for years, Xiaoxia Li, also from the Cleveland Clinic and co-corresponding author of the study, teamed up with Qin, a structural biologist, to identify a molecule to block the signaling pathway.

Using the previously solved crystal structure of the IL-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) complexed with IL-17A, the team virtually screened small molecules capable of blocking this interaction. After identifying several candidates, the researchers tested the inhibition efficacy of each and found that cyanidin binds to IL-17RA to block IL-17A binding. “We thought it was very exciting and also very interesting,” said Li.

Using mouse and human cells, the researchers validated cyanidin as an inhibitor of IL-17A activity. They then determined the efficacy of cyanidin to treat inflammation in diseases related to IL-17A. Indeed, mice with psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, and obesity-related asthma treated with IL-17A showed decreased symptoms.

IL-17A as a disease target is not new. The IL-17A antibody Cosentyx is approved by the US FDA to treat psoriasis and is being tested to treat other diseases, but producing antibodies for therapeutic use is expensive. “There is a really pressing need for cheaper drugs that can be used to treat these diseases,” said Sarah Gaffen from University of Pittsburgh, who was not associated with this study.

Qin, Li, and their team continue to optimize cyanidin for drug development. “The chemistry is challenging. You want to make sure that the properties are better than the natural compound, and that’s pretty difficult,” said Qin.

So, when will a new drug to treat inflammatory diseases be available? “That would depend on luck,” said Qin.