Looking O positive

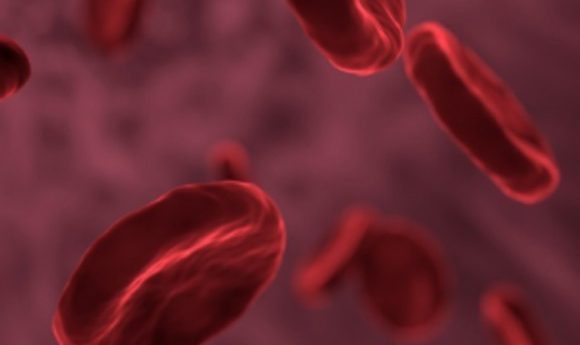

An enzyme for adjusting A and B blood types to the universal type O has been identified from the human gut microbiome.

Researchers have identified enzymes from human gut bacteria that can convert type A or B blood into type O nearly 30-times more efficiently than previously studied enzymes. The study, showcased at the 256th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (19–23 Aug, MA, USA), provides hope that blood will be able to be adjusted to the universal O-type in emergency situations in order to be administered to more patients.

“We have been particularly interested in enzymes that allow us to remove the A or B antigens from red blood cells,” commented Stephen Withers, study leader and professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of British Columbia (BC, Canada). “If you can remove those antigens, which are just simple sugars, then you can convert A or B to O blood.”

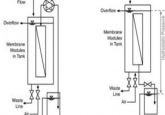

Withers collaborated with a colleague who specializes in metagenomics in order to sample the genomes of millions of microorganisms without the need for individual cultures. They then used E. coli to find genes that code for sugar-cleaving enzymes.

“This is a way of getting that genetic information out of the environment and into the laboratory setting and then screening for the activity we are interested in,” says Withers.

The successful enzyme was discovered from the human gut microbiome. The lining of the gut wall contains glycosylated proteins, termed mucins, providing an attachment point for the bacteria that feed off them. These sugars are similar in structure to those antigens found in type A and B blood and a particular family of bacteria was 30-times more effective at cleaving these antigens than previous enzyme candidates.

Withers now aims to develop and optimize these enzymes and test them on a larger scale in preparation for testing in a clinical setting.

“I am optimistic that we have a very interesting candidate to adjust donated blood to a common type,” concludes Withers. “Of course, it will have to go through lots of clinical trials to make sure that it doesn’t have any adverse consequences, but it is looking very promising.”

Watch the video overview of the research here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=JDM-DpAGh7U