Going into battle with antibiotics? Clostridioides difficile has the armor to protect itself

The superbug Clostridioides difficile (C. diff.) is resistant to all but three antibiotics, and researchers now reveal one of the defense mechanisms behind its success.

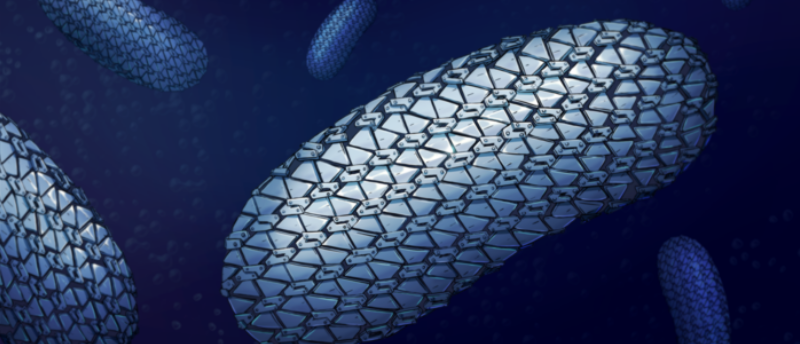

Researchers across several UK research institutions including Newcastle University have uncovered the protective surface covering C. diff., a superbug that infects the gut and can lead to life-threatening damage in the colon, for the first time. This layer, referred to as the S-layer, is mainly made of the surface-layer protein A (SlpA), tightly packed together to prevent molecules from entering the cell, and is one of the defense mechanisms that makes C. diff resistant to antibiotics.

Antimicrobial resistance is in the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity, according to the WHO (Geneva, Switzerland), so developing novel ways to combat bacteria is increasingly necessary. However, there are a variety of mechanisms that bacteria use to resist antibiotics, and superbugs such as C. diff. have multiple mechanisms to do so, making these infections more difficult to combat.

Using a combination of X-ray and electron crystallography, the research team was able to visualize the arrangement of the proteins in the S-layer and see how they linked together to achieve this protective pattern. The researchers compared the structure to chain mail, due to the flexible yet shielding arrangement covering the cell of the entire bacteria.

Are you as tough as a parasite?

Are you as tough as a parasite?

Researchers examined the effects of temperature variation on water fleas and find that infectious disease parasites may be better able to cope with unpredictable climate change than their hosts.

“I started working on this structure more than 10 years ago, it’s been a long, hard journey but we got some really exciting results!” says Paula Salgado (Newcastle University, UK), corresponding author on this study. Salgado explains that the “S-layer from other bacteria studied so far tend to have wider gaps, allowing bigger molecules to penetrate.” This structure could explain why C. diff. is able to fend off antibiotics and molecules sent by the immune system to fight infection so effectively.

C. diff. causes an infection of the large intestine, which results in a range of symptoms varying from diarrhea to lesions in the gut and is resistant to most antibiotics. Antibiotics also kill helpful bacteria in the gut so using antibiotics to treat other diseases can give C. diff. the opportunity to grow and infect, causing further harm in the body leading to a cycle of recurrent infections.

This new insight into the protective chain mail structure shows promise for combating C. diff. by developing specific drugs to target this surface. “If we break these, we can create holes that allow drugs and immune system molecules to enter and kill it,” explains Salgado.

Rob Fagan (University of Sheffield) performed the electron crystallography analysis and said: “We’re now looking at how our findings could be used to find new ways to treat C. diff. infections such as using bacteriophages to attach to and kill C. diff. cells – a promising potential alternative to traditional antibiotic drugs.”