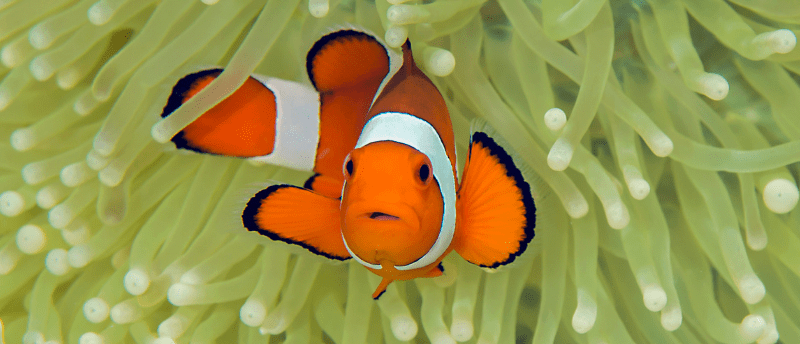

Genome analysis shows clownfish aren’t like other anemonefish

There’s no more clowning around, as the genome of the false clownfish has been reported at the chromosome-scale, providing a useful resource for many scientists.

Clownfish are used as a model species to answer biological questions, including understanding how fish in the coral reef will respond to climate change. Now, researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST; Japan) have published the genome of the rather unfortunately named ‘false clownfish’, or Amphiprion ocellaris, at the chromosomal level. This revealed 70 genes that separate clownfish from the rest of the anemonefish family, some of which are related to neurobiological function.

I’m sure for many people, clownfish are synonymous with Finding Nemo; however, there are in fact, two types of clownfish – the false clownfish and the true clownfish. Nemo and Marvin are true clownfish (Amphiprion percula) and are found around north-eastern Australia and some of the Pacific Islands, whilst the false clownfish live in coral reefs around Okinawa, Southeast Asia, the Philippines and north-western Australia. It is expected that their population will be affected by climate change as coral reefs decrease in size.

The two clownfish also look slightly different from each other. The percula has ten dorsal spines, thick black bands and orange around their eyes, and the ocellaris has 11 dorsal spines, thin black borders and dark coloring around their eyes.

“We can use the false clownfish as a model species for studying ecology, evolution, adaptation, development biology, and more,” said Vincent Laudet, an author of the study. The researchers hope the published genome of the false clownfish will be a useful resource across many fields of biological research.

Newly discovered marine microbes contribute to carbon cycling

Newly discovered marine microbes contribute to carbon cycling

A single-cell marine microbe produces mucus to feed on its prey in a process that also sequesters carbon, and could be a secret weapon to combat climate change.

Previous studies have published the genome of the true clownfish; however, studies on the false clownfish consisted of scattered genes with little understanding of their chromosomal arrangement. This paper reports a high-quality genome of the false clownfish at the scale of chromosomes and will enable comparative studies between the two clownfish and a better understanding of their different environments.

Both species of clownfish are part of the anemonefish subfamily, which has 28 fish species in total. “Evolutionary speaking, the two clownfish species are separated from the other 26 species in the subfamily,” commented Taewoo Ryu, who led this research project. “We wanted to find out what makes them special.”

The false clownfish in this experiment were collected from Onna-son (Japan) and studied using PacBio long-read sequencing and Hi-C chromosome conformation capture techniques to construct the genome of the Amphiprion ocellaris.

The researchers uncovered 70 genes that were only present in the genomes of the two clownfish, and not the rest of the subfamily. Additionally, they observed a subset of genes related to neurobiological functions, which are likely to affect their behavior and ecology.

“We’ve already started generating results using the published genome and there is a huge capacity for further climate change research on this species,” concluded Tim Ravasi, the senior author of the paper. “This resource provides a new baseline to start other experiments.”