Love really hurts without you: oxytocin helps regenerate the heart

Oxytocin, the neurohormone responsible for pleasure, has been found to help regenerate cardiomyocytes in zebrafish and human stem cell cultures.

A new study from Michigan State University (MI, USA), led by Aitor Aguirre, has demonstrated that oxytocin could one day be used to promote heart cell regrowth following an injury, such as a heart attack. Oxytocin is known as the love hormone due to its role in generating pleasure, forming relationships and various other matters of the heart. But never has it been implicated in the organ to stimulate cell growth, until now.

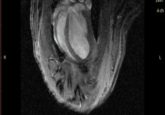

Following a heart attack, the cardiomyocytes, the cardiac muscle cells responsible for keeping the heart beating, degenerate rapidly and can’t regenerate themselves. However, previous studies have shown that a subset of cells in the outer layer of the heart, the epicardium, can transform into stem-like cells, called epicardium-derived progenitor cells (EpiPCs).

EpiPCs can regenerate cardiomyocytes and other types of cells in the heart; unfortunately, this is an inefficient process. Therefore, being able to efficiently trigger this stem-like transformation could be an effective therapy for those recovering from a heart attack.

To investigate how to efficiently trigger EpiPC production, the researchers turned to zebrafish, an organism famous for its regenerative powers. Although not prone to heart attacks, the fish can regenerate up to a quarter of their heart following an attack by a predator.

3 days after inflicting injury to the zebrafish heart via freezing, the researchers used qRT-PCR to show that messenger RNA expression for oxytocin was upregulated in the brain up to 20-fold. Using immunofluorescence techniques, they also demonstrated that oxytocin moved down to the epicardium, bound to oxytocin receptors, and triggered surrounding cells to transition into EpiPCs. These EpiPCs then moved deeper into the heart tissue to the middle layer, the myocardium, where they transformed into cardiomyocytes and blood vessels.

Oxytocin seemed to be responsible for triggering this process in zebrafish, but what about in human heart tissue?

Biochemists find a way to mend a broken heart

Biochemists find a way to mend a broken heart

Researchers developed a novel strategy to return cardiomyocytes to a stem cell-like state to promote the regeneration of heart muscle cells.

The researchers examined whether human tissue would be affected in the same way as zebrafish tissue. Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSCs), the researchers applied 15 neurohormones to observe their effects. Only oxytocin caused the hIPSCs to become EpiPCs and at a much faster rate than other molecules known to stimulate EpiPC production.

Additionally, when hIPCSs were genetically altered not to express the oxytocin receptor, they did not transition to EpiPCs. The researchers went further to identify the TGF-β signaling pathway as the link between oxytocin and EpiPC production.

“These results show that it is likely that the stimulation by oxytocin of EpiPC production is evolutionary conserved in humans to a significant extent,” reported Aguirre. “Oxytocin is widely used in the clinic for other reasons, so repurposing for patients after heart damage is not a long stretch of the imagination. Even if heart regeneration is only partial, the benefits for patients could be enormous.”

Further research is needed to investigate whether oxytocin would have the same stimulating effect in the human body as well as how it could be harnessed as a therapy.

“Next, we need to look at oxytocin in humans after cardiac injury. Oxytocin itself is short-lived in the circulation so its effects in humans might be hindered by that. Drugs specifically designed with a longer half-life or more potency might be useful in this setting. Overall, preclinical trials in animals and clinical trials in humans are necessary to move forward,” suggested Aguirre.