Craniopagus conjoined twins separated: the case of Safa and Marwa

Nine months and 50 hours of surgery later, 2-year-old identical twin sisters Safa and Marwa Ullah have left Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH; London, UK) following successful craniopagus separation.

Born by cesarean section in Hayatabad Hospital (Peshawar, Pakistan), the girls were healthy aside from one significant complication; they were joined at the head. This extremely rare complication meant that their brain tissue and blood vessels were intertwined and skulls were fused to form a long tube. The craniopagus conjoined twin girls were connected crown-to-crown and facing opposite directions, meaning the two sisters had never seen each other’s faces.

Lead by pediatric neurosurgeon Owase Jeelani and plastic surgeon David Dunaway, a group of almost 20 specialists formed the GOSH team responsible for separating the girls in a procedure spanning three operations and utilizing the latest in 3D printing and virtual reality technology.

Following their successful separation, the twins left GOSH in mid-July. Though they will still need follow up appointments and physiotherapy, their mother is extremely excited and looks forward to the future with the girls.

How do conjoined twins form?

Conjoined twins are formed from the incomplete separation of one fertilized egg, meaning that genetically, the twins are virtually identical. It is unknown exactly how or why the bodies fuse, though it is generally believed to be either due to the split happening later than normal and the twins only partially dividing or the twins being too close together following the split and the body parts that are in contact merging as they grow.

Each case of conjoined twins is unique, though, more often than not, the fusion occurs on the lower body – most commonly the chest, abdomen or pelvis. Craniopagus conjoined twins, that being twins that are fused at the head, are rare and usually account for one in every 2.5 million births. Of that, it is then rare for the twins to survive longer than 24 hours and there have been only 60 reported cases of successful separation of craniopagus twins since 1952. With two such separations already under their belt, GOSH is already a world leader in this surgery having performed the procedure more than any other medical institution.

20948

Putting it in 3D

Usually, the ideal time for separating craniopagus twins is when they are aged between 6–12 months. Younger brains and vasculature have greater regenerative potential and the skin and bones are likely to heal and grow better. Despite being over 2 years old and past the optimum age for such an operation, the advances in technology that have occurred in the timeframe have given the girls, and their surgical team, a distinct advantage.

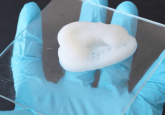

Using the latest in 3D technology, the team were able to develop 3D models of the girl’s heads, including their interlocked brains, fused skulls and connected skins. Head of the modeling team, craniofacial plastic surgeon Juling Ong highlighted the benefits of the rapidly developing technology. “These are really unique cases and it’s not something that we get taught in medical school. With this software, we can make a realistic computer model to look at the extraordinary anatomy of these children and plan our surgeries beforehand,” he commented.

3D printing technology meant that the surgeons were able to print a replica of the twins’ unique anatomy, allowing them to gain a tactile understanding of what they were dealing with long before they entered the operating theater. “To be able to see and visualize this and play with these models before the surgery makes an enormous difference to how we plan and do this operation,” explained Jeelani. “What we need to achieve is, in effect, to sort of untwist the brains. And that’s pretty difficult to do just in your head.”

In addition to recreating physical models, the team was able to enter the virtual world, seeing the complex, intertwined vasculature shared by the girls through a pair of virtual reality goggles. “This is clearly the way of the future,” enthused Jeelani. “We are blessed here [at GOSH] in terms of the engineers and the software specialists – the skill sets they bring to the equation are skills that we as doctors with our medical training don’t have.”

In this interview from our sister site 3DMedNet, Ong discusses the use of 3D-printed models for the rehearsal of complex surgical cases involving children, focusing on the case of Safa and Marwa discussed in this article.

- Not-So Identical Twins

- It’s a twin thing: uncovering the biological effects of space travel

- The curious case of the Zika twins

Separating the vasculature

Despite the high-risk nature of the procedure, all involved were keen to proceed with the complex operation. “It is clearly very difficult to go through life when you are joined together like that, so it does make a persuasive case in favor of attempting the separation and the family are very clear on that,” commented Jeelani.

“Clearly I think life being separate is better than being joined together. If we felt there wasn’t a very high chance that we could do it safely, we would think hard about whether we should do it at all. The whole team feels there’s an excellent likelihood of a successful separation here,” added Dunaway.

If you wish to hear more from Dunaway, he will be speaking at the inaugural 3D Med Live event next October, commenting on the use of 3D printing in surgery and its importance for cases such as this. Register for the event here.

The first two of the three operations involved separating the initially entwined vasculature, starting with the arteries. The twins shared numerous arteries and each cut carried a significant risk of brain damage. Over several hours, each of the shared arteries were clamped and sealed by the neurosurgery team while, to the side, Dunaway constructed a frame from the sections of removed skull that could be detached during later operations. As the first surgery came to a close, a sheet of soft medical plastic was placed between the two brains, preventing the brains from re-connecting in the time to the next surgery, and the crafted skull frame was re-attached.

One month after the first operation, the team entered the operating room once again, this time to separate the veins. As soon as the skull frame was detached, things began to go downhill; in the time since the previous operation, clots had formed in the veins of Safa’s neck, restricting the draining of the blood from her brain. This meant that she had been shunting blood to Marwa and, after the skull was detached, the girls began to bleed. Later in the operation crisis occurred again, as Marwa’s heart rate dropped. As it was clear to the surgical team that she was the weaker twin, they gave Marwa a key shared vein, increasing her chance of survival though having a serious impact on the health of Safa.

Over 20 hours later, at 6:30 the following morning, the operation was over and the twins stable. However, the next afternoon Safa had a stroke in the region of the brain where the key vein had been. Following 2 days in a critical condition, she showed signs of recovery and was taken off the ventilator though still had some weakness in her left arm and leg.

20949

The final separation

Six weeks before the final operation, the plastic surgery team had inserted four small plastic sacs under the skin of the girl’s foreheads and at the posterior of their shared skull. This was in order to promote skin growth, expanding the tissue so that, when they were finally split, there was enough surface area of skin to cover the top of their two individual heads.

“They have a tiny little port attached to them through which we can inject saline,” Dunaway explained. “The idea is that we will gradually inject the tissue expanders and they will blow up like a balloon and the skin over the top of them will stretch.”

Moved forward by 4 weeks due to Marwa’s struggling heart, the final separation took place in February of 2019. Over 7 hours, all remaining connecting tissue, brain and bone were severed and, for the first time in their life, the twins could be separated. “It was a very emotional moment,” commented Dunaway. “We’ve been working a long time to get them here – they’ve been through so many operations and now it’s worked.”

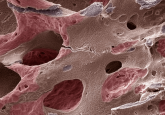

Moving Marwa to her own operating room, the team split in two and worked simultaneously to reconstruct each twin’s skull. Each brain was enclosed in a casing of tough dura, with fragments of skull jigsawed on top to create an archipelago of bone fragments. In order to have enough skull to cover the girls’ newly separated heads, the fragments of skull had to be split in two.

“The skull is usefully designed in three layers: the inner and outer layers are very thick tough bone, but in between is like a honeycomb so you can split it. It is half the thickness but it means we should be able to cover nearly all the head with bone,” explained Dunaway.

The gaps in the bone fragments were seeded with bone cells which should, in the coming months, close up to leave each twin with a complete skull. Thanks to the previously inserted tissue expanders, there was enough skin to cover each reconstructed skull and finally, after 17 hours in theatre, the complex procedure was complete.

20961

Moving on

Five months after their separation it is time for the twins to leave hospital. During recovery they both required skin grafts and daily physiotherapy to help them learn to hold their heads up, roll and sit up. With regular checkups and further physiotherapy planned, it is not necessarily going to be an easy few months, though both doctors and parents remain hopeful and plan to return to Pakistan in early 2020.

“It may have been difficult to provide the care to keep them fit and healthy. Clearly, they are going to face some challenges but I think overall, it’s a positive outcome for them. They have a chance of leading happy lives now,” commented Dunaway.

Dunaway and Jeelani have since set up a charity named Gemini Untwined (London, UK) in order to bring together research on conjoined twins and help to raise money for future operations so there is not the need for the delay seen in the case of Safa and Marwa.

“What we would like to see is that we don’t have this potentially damaging delay in treating children, and a research arm giving us much more information,” Dunaway concluded. “There is so much we don’t know about conjoined twins, we think we’re doing it the right way but we really need to understand that in a scientific way.”

Find out more about Professor David Dunaway’s work using 3D printing technologies for surgery at 3DMedLIVE: 3D printing in surgery (2–3 October 2019; London, UK), accredited by the Royal College of Surgeons of England for up to 10.5 CPD points. Visit www.3dmedlive.com