The ancient canine cancer that has spread worldwide

Scientists have shed new light on the fascinating beginnings of canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT), an infectious cancer that is spread exclusively between dogs.

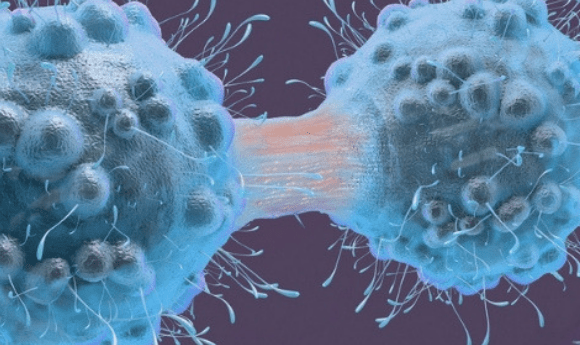

CTVT is a cancer specific to dogs that is spread sexually, via the transmission of living cancer cells. The tumor originated in a so called “founder dog” in which the cancer developed and then transmitted to other dogs. CTVT cells found in dogs today are not cancer cells from the dog’s own body, but from the original founder dog, changed only by mutations that have occurred over time. In nearly all cases, the cancer dies when the host passes away, however, CTVT bypasses this by transmitting to other hosts.

Backed by the Wellcome Trust, the Leverhulme Trust and the Kennel Club Charitable Trust (all London, UK), scientists at the Transmissible Cancer Group (TCG) at the University of Cambridge (UK) have shed more light on this unique cancer. By comparing tumor samples from 546 dogs worldwide, the team has ascertained how CTVT arose and the mechanism by which it spread.

Researchers analyzed somatic mutations extracted from the protein-coding genomes of the tumor samples. Using this data, they were able to construct a phylogenetic tree to track the evolution of the mutations that have arisen in CTVT. From this, the team were able to approximate that the cancer first emerged between 4000 and 8500 years ago. The phylogenetic tree has also allowed significant insight into the route of CTVT’s spread.

“This tumor has spread to almost every continent, evolving as it spreads,” explained Adrian Baez-Ortega (TCG). “Changes to its DNA tell a story of where it has been and when, almost like a historical travel journal.”

-

Overcoming anticancer drug restrictions in veterinary medicine

-

Tumor-targeting protein could be future of personalized cancer therapy

-

Vest of interest for personalized radionucleotide therapy

There is evidence that the maritime activities of humans and their canine companions helped facilitate the spread of CTVT across the globe. The cancer first spread from Europe to the Americas around 500 years ago, when settlers arrived by sea. From the Americas, CTVT spread to Africa and into the Indian subcontinent, both areas that were European colonies.

As well as investigating the tumors’ historical spread, researchers also focused on identifying unique carcinogenic signatures found in CTVT’s genome. Exposure to UV light was one biological process shown to have damaged the cancer genome, as well as a distinctive molecular signature – ’Signature A’ – which is unlike any seen previously.

“This is really exciting – we’ve never seen anything like the pattern caused by this carcinogen before,” commented Elizabeth Murchison (TCG). “It looks like the tumor was exposed to something thousands of years ago that caused changes to its DNA for some length of time and then disappeared. It’s a mystery what the carcinogen could be. Perhaps it was something present in the environment where the cancer first arose.”

CTVT’s days may be numbered, analysis showed no evidence for either positive or negative selection, suggesting that the cancer is accumulating more and more deleterious mutations meaning it is becoming less fit for its environment. However, despite the cancer gradually deteriorating, it will still be thousands of years before it vanishes.