Quality control: the dark side of cell culture

Cell culture is integral to the future of drug discovery, but it suffers from a lack of reproducibility owing to inconsistent quality control.

3D cell models are showing ever increasing promise in scientific research, particularly given the continued issues with translating basic research into new therapeutics. However, the explosion in research utilizing cell culture in this way has not been matched by efforts to ensure quality control of the cells in question. This poses even further risk to the successful translation of research, with a lack of quality control resulting in a lack of reproducibility.

Quality control in cell culture includes accurately identifying cells, as well as ensuring there is no contamination and the cells do not change excessively during the culture period. This is difficult when there are no absolute guidelines on methods to do this, which results in quality control procedures varying between laboratories. Sharing of cell lines between laboratories is also common practice.

“Cell culture sometimes feels like a black art, with everyone having their own preferred method,” commented Derfogail Delcassian, a researcher at MIT (MA, USA).

But why, when cell culture has been around for decades, does quality control remain such an issue? There are a few reasons why it might still on the back burner. One potential is that the work is much less ‘glamorous’ than the work of using those cell culture methods to discover potential new life-saving drugs, so less time is allowed for it. Also, work in this vein is less likely to result in a high impact publication.

Another reason for the continuing problem could simply be that researchers are often not aware of the issue. For example, one of the biggest threats to cell cultures is mycoplasma (or Mollicutes), which are not detectable via light microscopy, making them difficult to detect.

Mollicutes – not so ‘cute’

Cell cultures can become infected with mycoplasma through the original tissue isolate, culture reagents, human error or cross-contamination. What’s more, mycoplasma are often resistant to antibiotics.

With some research suggesting over 10% of cell lines are contaminated, this is clearly an important issue. Current detection methods for mycoplasma, such as culture or ELISA, are time-consuming and expensive, and thus not ideal. However, the global mycoplasma testing market is expected to double to US$1358.2 million by 2024, suggesting new techniques will be brought to the fore.

One of the new techniques already showing promise is Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy, for which preliminary results are now available. Another is qPCR, which has been shown to exhibit high sensitivity at detecting mycoplasma. However, while the availability of these techniques bodes well for the future, it does not solve the problem of past research feeding into future work. This issue has come to particular prominence in cell line authentication.

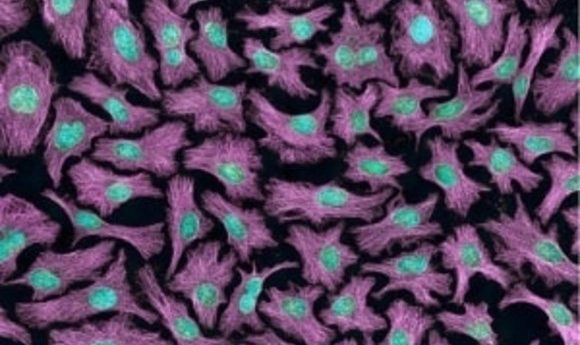

The wrong cell lines

The problem with identification/authentication is potentially more challenging and far-reaching into the literature than microbial contamination. It’s very easy for cell lines to be infiltrated by immortal ones, for example HeLa cells. This problem is widespread – one study published in 2017 identified over 30,000 publications discussing the wrong cells, and those studies have been cited by at least half a million others. This is something that is likely to be supporting the current replication crisis.

“Most scientists don’t intentionally publish findings on the wrong cells,” commented Serge Horbach, co-author of the 2017 study (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). “It’s an honest mistake. The more concerning problem is that the research data is potentially invalid and impossible to reproduce. What’s even scarier is that we’ve known about these wrongly identified cells for half a century, yet many researchers aren’t aware of this. New articles are published every week about misidentified cells.”

Cell line authentication can be achieved in a variety of ways, for example short tandem repeat profiling. However; time availability, the pressure to publish positive results and costs can be a barrier to wide and consistent take-up of these techniques. It is likely that to move forward, researchers might need to follow examples from fields such as cell therapy, where strict quality control rules are set by governmental bodies, such as the US FDA.

But how do we correct past literature? “One solution would be to put a disclaimer on all 30,000 publications explaining that they report on the wrong cell line,” suggested Horbach and co-author Willem Halffman. “It would then be up to readers to decide whether it’s a problem or not, because sometimes it really doesn’t matter.”

Meanwhile, various initiatives, such as PRINTEGER and the International Cell Line Authentication Committee, are underway to improve things for future research. Some aim at improving protocols and the laboratory environment while some, such as the Cellosaurus and the Cell Line Data Base, aim to provide a knowledge resource. These resources also aim to help solve the naming issue, whereby the lack of guidance has led to duplication of names, and thus further issues with misidentification.

While it might not be the glamorous side of cell culture research, quality control is clearly coming to the forefront. It’s time to look ahead with interest to updates in this field – both to improve quality control going forward, and to address potential issues going back.