Scientists uncover L. reuteri’s role in oxytocin secretion

Scientists discover oxytocin is produced in the small intestine and that its secretion is mediated by the gut bacterium Limosilactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri).

Over the last decade, there has been a growing awareness that the effects of the gut microbiome extend far beyond the gastrointestinal system and reach other organs. Researchers at the Baylor College of Medicine (TX, USA) have turned their attention towards L. reuteri, a bacterium that has been shown to influence the function of several organ systems and have beneficial effects on the body. This microbe piqued their interest as some of its benefits require oxytocin signaling. In a recently published study, the team set out to understand how a gut microbe such as L. reuteri could impact oxytocin signaling, a hormone typically produced in the brain.

Understanding the health impacts of these host–microbe interactions could allow us to manipulate gut microbial functions and regulate the physiology of multiple organs. Sara Di Rienzi, co-corresponding author, explained, “Researchers have found that these bacteria reduce gut inflammation in adults and rodent models, suppress bone loss in animal models of osteoporosis and in a human clinical trial, promote skin wound healing in mice and humans and improve social behavior in six mouse models of autism spectrum disorder.”

Oxytocin is produced in intestinal epithelium

The team began by analyzing publicly available single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-Seq) datasets of the intestinal epithelium to determine which genes are expressed in that tissue. They found that genes encoding for oxytocin, OXT, was evolutionarily conserved. Human datasets showed that the highest number of OXT-positive cells were in the small intestine, indicating that oxytocin is produced in the intestinal epithelium.

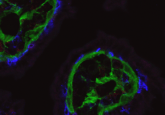

To provide further evidence, they performed immunostaining and fluorescence imaging on human intestinal tissue, observing oxytocin staining in the epithelial layer of the stomach as well as the large and small intestines. As was found in the scRNA-Seq data, the greatest number of oxytocin cells were present in the small intestine.

Some of the investigated scRNA-Seq datasets were derived from intestinal organoids created from epithelial stem cells. Without the presence of other gut cell types, these cells would differentiate to produce only the epithelial layer, so if oxytocin is produced in these organoids, then the gut epithelium is enough to stimulate its production. Reverse transcription quantitative PCR on intestinal organoids indicated this was the case, showing higher levels of OXT transcripts in differentiated (mature) organoids than in undifferentiated (primarily stem cells) organoids, suggesting that oxytocin’s secretion could be directly or indirectly stimulated by L. reuteri.

L. reuteri promotes oxytocin secretion from intestinal epithelium

The next step was to determine whether L. reuteri could stimulate oxytocin secretion from the gut epithelium. To do so, they applied L. reuteri cell-free conditioned medium made up of a mix of proteins, metabolites, nucleic acids and other molecules released by L. reuteri to human and animal intestinal segments, which all showed a significant secretion of oxytocin throughout the small intestine.

To identify which cells produce oxytocin in the intestinal epithelium, the researchers returned to the scRNA-Seq datasets and found that OXT was predominantly expressed within enterocyte clusters. They also co-stained human small intestine tissue with oxytocin and enterocyte markers and observed co-localization. This data suggests that oxytocin in the small intestine is produced and secreted by enterocytes.

Emotional contagion: the evolutionarily conserved role of oxytocin

Emotional contagion: the evolutionarily conserved role of oxytocin

A new study delves into the evolutionary conservation of emotional contagion and the role oxytocin plays in empathy.

Secretin receptor signaling induces oxytocin release

Whilst enteroendocrine (EEC) cells were ruled out as a producer of oxytocin in the small intestine, its secretion by L. reuteri from organoids did require increased EECs, which made the researchers question whether an EEC-derived product mediates L. reuteri-driven release of oxytocin.

In the brain, the peptide hormone secretin can release hypothalamic oxytocin. Secretin is also produced by EEC cells in the gut. It was therefore hypothesized that secretin could promote the release of oxytocin in the small intestine. The researchers demonstrated that the addition of secretin stimulated the release of oxytocin from intestinal organoids and intestinal tissue and showed that a competitive inhibitor of secretin blocked oxytocin release.

What do these findings mean?

Through their study, the team showed that L. reuteri stimulates EEC cells in the intestine to release the gut hormone secretin, which in turn stimulates enterocytes to release oxytocin.

Robert Britton, co-corresponding author of the paper, said, “We are excited about these findings. These bacteria have positive effects in various parts of the body, but it was not understood how that happened. Our findings reveal that oxytocin is also produced in the gut and a new mechanism by which L. reuteri affects oxytocin secretion. Now, we are working to identify potential treatments for autism spectrum disorders using a new mouse model deficient in intestinal oxytocin to gain a new understanding of the connection between oxytocin produced in the gut, social behavior and the brain.”