Unraveling the history of tuberculosis one bone at a time

Researchers uncover ancient transmission chains of tuberculosis, by analyzing the DNA of humans excavated from archaeological sites across Colombia.

Although tuberculosis is one of the biggest infection-related causes of death worldwide, its evolutionary history is yet to be fully understood. A team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany), and Arizona State University (AZ, USA), have found clues in the ancient DNA of individuals showing signs of skeletal tuberculosis.

A study in 2014 discovered that the likely origin of tuberculosis in Peru was from marine mammals, such as seals and sea lions, finding that the bacterium went on to infect humans living in coastal areas prior to European colonization.

This was confirmed by the researchers of the current study, who also identified three new ancient pre-contact era South American tuberculosis genomes by analyzing the DNA of humans who lived away from the coast, including two sites in the highlands of the Colombian Andes. Using archaeological evidence and stable isotope data, they further determined that those living inland did not come into contact with marine mammals.

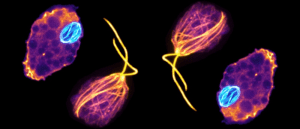

Shapeshift, eat brains, disclose evolutionary secrets: a day in the life of an amoeba

A unicellular organism that can rebuild itself into a different organism, could provide a greater understanding of the fundamental rules underpinning life on Earth.

“All of these new three ancient tuberculosis genomes resemble M. pinnipedii – the same tuberculosis variant found in the ancient coastal Peruvian individuals and in modern-day seals and sea lions,” explained Tanvi Honap, the co-lead of the study.

Importantly, these findings suggest that the infections were caused by the bacterium “jumping” species across long distances, as opposed to direct transmission from marine mammals.

“Colombia has a wide variety of terrestrial mammals, so M. pinnipedii could have been brought inland via the animal life,” Honap commented. “Or in a more likely scenario, it could have been brought inland via human-to-human transmission facilitated by trade routes, or a combination of both!”

The scientists view this discovery as a starting point for deeper learning about the ecology of the disease prior to European colonization.

Anne Stone, a co-author of the study, concluded: “It’s an exciting time in ancient DNA research, as we can now look at genome-level differences in these ancient pathogens and track their movements across continents and beyond.”