Bonding with your baby: more than a feeling?

Babies could be ‘on the same wavelength’ with adults during play, as the two brains display neural synchrony during direct interaction.

New research from the Princeton Baby Lab (Princeton University, NJ, USA) suggests that babies are more in sync with adults than originally thought and during direct interaction a pair may really be ‘on the same wavelength’.

With a focus on early psychological development, the Baby Lab research group works with babies to study how they gradually learn to understand the world and all in it. In their latest study, a first-of-its-kind, the team measured the real-time neural activity of babies and adults as they interacted.

“Previous research has shown that adults’ brains sync up when they watch movies and listen to stories, but little is known about how this ‘neural synchrony‘ develops in the first years of life,” commented first author Elise Piazza.

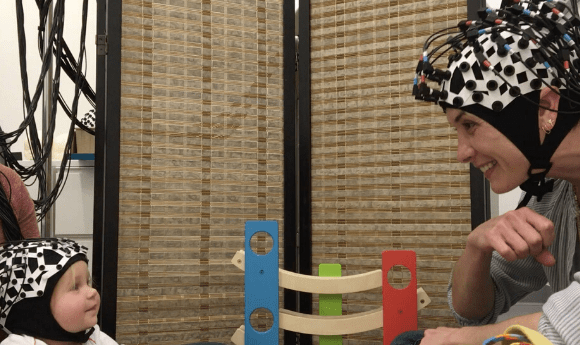

Past research into neural synchronicity has primarily been done in adults, often recording neural activity with functional MRI scans while the participants watched a common movie. As this technique would be impossible to conduct with young children, the researchers developed a new dual-brain neuroimaging system that utilizes functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Similar to functional MRI, this technique records blood oxygenation as a proxy for activity. However, instead of being limited to the confined space of a scanner, recordings can be taken using brain caps, like those used in EEG recordings.

The experiment itself was split into two parts; for the first half, the baby and the experimenter would directly interact, by playing with toys, singing or reading the book ‘Goodnight Moon’. During the second half, the child would play with their parent while the experimenter read a story to another person in the room.

- Babies getting into monkey business

- The brain’s social network

- Do c-section babies have a weaker immune system?

Published recently in Psychological Science, the results showed that when directly interacting, certain regions of the baby’s and adult’s brains displayed neural synchrony. When facing away from each other, this apparent connection disappeared.

Though the general results fit the team’s expectations, the regions of the brain involved caused some surprise. The prefrontal cortex, an area responsible for skills thought to be underdeveloped during infancy, showed particularly strong coupling. They also found that, at times, it appeared that the child was influencing the adult more so than the other way around.

“While communicating, the adult and child seem to form a feedback loop,” explained Piazza. “That is, the adult’s brain seemed to predict when the infants would smile, the infants’ brains anticipated when the adult would use more ‘baby talk,’ and both brains tracked joint eye contact and joint attention to toys. So, when a baby and adult play together, their brains influence each other in dynamic ways.”

The Baby Lab team hypothesize that this early life neural synchrony may have vital implications for later life development, particularly regarding the development of social skills and language acquisition. They hope to continue investigations into this synchronicity and find out how it relates to learning. In addition, they hope to use the two-way, real-time approach to see how coupling between child and caregiver can break down during atypical development – particularly in cases of children with autism spectrum disorder.