Can you teach a jellyfish new tricks?

Jellyfish demonstrate you don’t need a brain to learn from experience.

Jellyfish are some of the oldest animals inhabiting Earth and have existed for more than 500 million years (appearing more than 250 million years before the first dinosaurs!). Researchers at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark) and Kiel University (Germany) have found that we’ve been underestimating what jellyfish are capable of, demonstrating that they can learn from past experiences. This finding sheds light on the evolutionary roots of learning and memory.

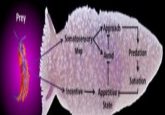

This study looked at the Caribbean box jellyfish (Tripedalia cystophora); these jellyfish are no bigger than a fingernail and live in mangrove swamps, using 24 eyes to navigate through the murky swamps and catch prey. The researchers showed that these jellyfish can learn to avoid obstacles through associative learning, whereby mental connections are formed between sensory stimulations and behaviors. This challenges the previous understanding that jellyfish have limited learning abilities due to their simple nervous system and lack of a brain.

Learning about cellular senescence from squishy sea creatures

Learning about cellular senescence from squishy sea creatures

Tiny sea creatures give insights into how the biological processes of healing and aging are intertwined, providing a new perspective on how aging has evolved.

To investigate the learning capabilities of the jellyfish, the researchers dressed a round tank with grey and white stripes, simulating their natural habitat and mimicking the appearance of mangroves in the distance. They watched the jellyfish navigating the tank for 7.5 minutes. Initially, the jellyfish would bump into the stripes frequently; however, by the end of the experiment, the jellyfish had increased its average distance to the wall by 50%, quadrupled the number of successful pivots to avoid colliding with the wall and halved its time in contact with the wall. These observations indicate that jellyfish can learn from experience through a combination of visual and mechanical stimuli.

In order to understand the underlying process of this learning, the researchers isolated the jellyfish’s visual sensory centers called rhopalia, which each house six eyes and produce pacemaker signals that determine the pulsing motion that helps jellyfish swerve away from obstacles.

Stationary rhopalium were shown moving grey bars to mimic the action of approaching an object. When shown light grey bars, imitating an obstacle in the distance, this structure did not respond. After training rhopalium with weak electrical stimulation (acting as the mechanical stimuli of a collision) when the bars approached, the rhopalium generated signals to dodge the obstacle represented by the light gray bars. This shows that the rhopalium serves as the learning center in jellyfish and provides more evidence that jellyfish have associative learning capabilities.

“It’s surprising how fast these animals learn; it’s about the same pace as advanced animals are doing,” explained senior author Anders Garm (University of Copenhagen). “Even the simplest nervous system seems to be able to do advanced learning, and this might turn out to be an extremely fundamental cellular mechanism invented at the dawn of the evolution nervous system.”