How felines found their way

Researchers used ancient mitochondrial DNA to track cats as they clawed their way into human lives thousands of years ago and to follow their advance across the old world.

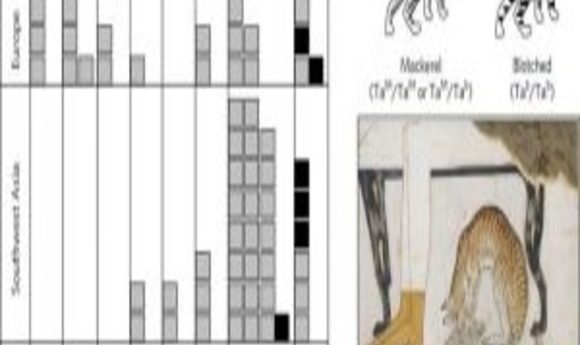

Ottoni’s team tracked the blotched tabby markings over time (1).

The advent of agriculture marked the dawn of human relationships with feline friends. With their ability to hunt crop-eating and disease-bearing rodents, cats started a millennia-long coexistence in human societies. Fast forward to the present day and they are a mainstay in Western society, with one in three American households owning a cat.

Questions remain about where modern domestic cats originated and how they conquered the Old World. Now, researchers present a phylogeographic distribution map, showing that modern cats originated in two different locations, creating two waves of dispersal.

“Studies have overlooked the cat in domestication research,” said lead author Claudio Ottoni from The University of Oslo. “They occupy such a prominent position in our society, and we felt they were neglected in domestication studies.”

To track how felines dispersed across the world over time, Ottoni and his colleagues mined mitochondrial DNA samples from 352 ancient cats spanning over 9,000 years. “There were technical challenges relating to DNA preservation in hot climate regions,” said Ottoni. “We developed a strategy targeting short fragments of the mitochondrial DNA to obtain all necessary information.”

The team found two distinct mitotypes among cats, representing two separate origins. The first domesticated lineage originated in modern-day Turkey around 8000 B.C. and spread to Europe 4,000 years later. The second lineage first appeared at around 700 B.C. in Egypt and expanded across Europe to become more dominant over the next few thousand years.

Human connectivity was key for driving this dispersal. “What’s striking is that many of these remains were found at ports, indicative of how cats were spread using trade routes,” said Ottoni. “One specific example was finding feline remains with the Egyptian mitotype dating to the 7th Century A.D. at a Viking port.”

Ottoni’s team also looked at phenotypic variation, tracking a popular coat variation in domestic cats—tabby markings. Often used to distinguish wild and domestic cats, the blotched SNP Taqpep gene acted as a useful phenotypic marker. “We found that the allele responsible for blotched tabby marking appeared no earlier than the Middle Ages. This suggests that prior to this, we were only selecting for behavioral traits when breeding, not physical.”

Looking ahead, the researchers hope to use feline genomic DNA to track hybridization between wild and domesticated cat species. “We want to investigate evolutionary factors like hybridization and if they occurred in the history of domestication, how they occurred and which populations they affected,” said Ottoni.