Translating the power of genomic sequencing from research to clinical care

Diagnostic rates of genetic diseases could be increased by up to 32% with improved structure and guidelines for reanalyzing patients’ genomic sequencing data.

When new variants in known genes are reported or a new gene is associated with a particular condition, laboratories can re-run patients’ genomic data that has been previously analyzed to check for the variant’s presence.

However, research led by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) and the University of Melbourne (both VIC, AUS) found that there were inconsistencies surrounding the decision to reanalyze genomic data.

While previous studies have demonstrated that large proportions of patients do not receive a diagnosis when genomic data is first analyzed, despite a diagnostic yield of up to 68% depending on the genetic condition, reanalysis could be instrumental in affecting patient outcome by guiding treatment options. However, this is not currently a compulsory measure for laboratories.

“Studies show that systematic data reanalysis leads to considerable increases in genetic diagnosis rates between 4–32%. Yet it is time intensive and is not currently feasible for most laboratories to implement,” explained lead researcher Danya Vears (MCRI). “Few policies address whether laboratories have a duty to reanalyze and it is unclear until now how this has impacted clinical practice.”

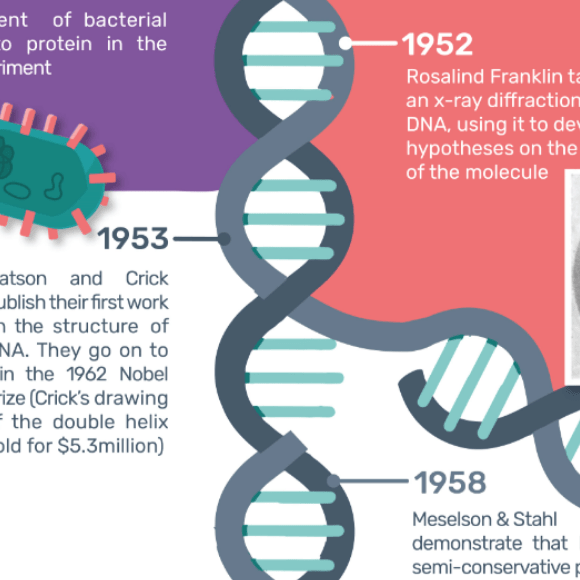

For this year’s DNA day, we put together a timeline of the history of DNA discovery, starting in 1944 when it was first proved to be the agent of bacterial transmission.

The study, published in Familial Cancer, was based on the experience of 31 genetic health professionals from across Europe, Australia and Canada. They discovered that most patients were initiating reanalysis after being told by their clinician to revisit the genetic service when new information was discovered, or after a certain period of time had passed.

“Some of our participants felt that this system was working quite well and that patients were returning,” continued Vears. “Yet others raised questions around patients’ abilities to proactively request this service. This could be due to their lack of understanding of what a negative result might mean because it places additional pressure on patients or families to remember to return when they are already dealing with a complex medical situation.”

There was a consensus that the best-case scenario would be if laboratories initiated the reanalysis process, though the technology is not yet in place to make this a reality.

Vears concluded by saying that genetic services should have clear and consistent guidelines related to the reanalysis of genomic data so that patients do not miss the opportunity for updated information on their genetic condition. She believes that translating the power of genomic sequencing from the research content into clinical care is a major goal of researchers and health-care providers.

The history of DNA discovery

The history of DNA discovery