The epigenetics of marijuana use

Several states recently legalized marijuana. This may reduce legal costs for states and generate tax revenue, but what does research show about its effect on health?

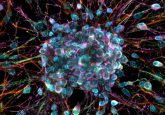

Cannabinoid receptor expression in the human brain.

Image courtesy of Yasmin Hurd.

In November 2016, California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada legalized medicinal and recreational marijuana, while Arkansas, Florida, and North Dakota legalized marijuana for medicinal purposes. There are good arguments for cannabis legalization from a criminal justice perspective: putting people in jail for smoking a joint consumes an enormous amount of law enforcement resources that could arguably be put to better purposes. “But I’m concerned about what the ramifications are from a health perspective,” said Barry Setlow, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the University of Florida. “State legislatures have embraced medicalization and legalization without a tremendous amount of forethought about the consequences a step or two down the road.”

Compared to tobacco, relatively little is known about the long-term effects of cannabis use, partly because it is classified as a schedule 1 drug by the Drug Enforcement Administration—a category reserved for drugs with the potential for abuse and no demonstrated medicinal value.

Researchers who want to study cannabis face onerous bureaucratic procedures to access it. These restrictions create a catch-22: It’s challenging to do the studies to demonstrate any medicinal value cannabis may have without access to the drug. It’s also difficult to determine any threats to public health that legalization may bring.

“The legalization of cannabis has been about money and perception,” said Yasmin Hurd, director of the Addiction Institute at Mount Sinai Behavioral Health System. “Lobbyists for the marijuana industry have really promoted the idea that marijuana is no worse than alcohol or nicotine. The lobbyists were very effective in convincing states that they could earn a lot of money off the taxes for the sale of marijuana.” And so policy decisions were guided by anecdotal information and pressure from lobbyists. “Policies shouldn’t be made that way—it should be about evidence-based medicine,” she said.

Epigenetic Changes Underlie Addiction

Turning to the evidence raises some serious concerns for public health. Hurd’s team recently showed that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of marijuana, increases heroin self-administration in adults who were exposed to THC as adolescents. “Marijuana in the young brain acts like a neurobiological gateway,” Hurd explained. THC even has cross-generational effects (1,2); adult rats whose parents were exposed to THC as teens self-administer more heroin, suggesting that THC affects the germline.

Epigenetic changes aren’t unique to marijuana. Hurd’s team recently published a pattern of epigenetic changes they found in the brains of human heroin users (3) that affected the activity of genes that regulate glutamatergic signaling.

“We study the brain of heroin abusers who died of overdoses and other causes because it’s a reality that keeps us grounded on the key issue of addiction,” Hurd said. “There is an urgency with addiction that isn’t really impressed on enough, in terms of the mortality, morbidity, and the problems that it causes.” Deaths from opioid overdoses are currently at an all-time high. Since 1999, the number of overdose deaths involving opioids has quadrupled (4).

Using lab rats that could control their heroin intake at will, Hurd’s team found that epigenetic changes in the rats’ brains were similar to those in human heroin-addicted brains, confirming that heroin was the cause of these epigenetic changes.

Gabor Egervari, the lead graduate student on the project, next used a small molecule called bromodomain inhibitor JQ1, which is used by cancer researchers to erase faulty epigenetic marks in cancer cells, to reverse the epigenetic changes in the brains of heroin-addicted rats. The drug inhibited heroin-seeking behavior and consumption in rats, indicating that it could be a candidate for reducing heroin-seeking behavior in human addicts too.

Medical Marijuana for Treating Heroin Addiction?

Hurd’s team also studies the effects of cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive substance in the cannabis plant. “We were surprised to find that it did not increase heroin self-administration,” Hurd said. Even days and weeks after CBD was administered, it continued to reduce heroin-seeking behavior triggered by environmental cues (5) .

“Relapse for most addicts is related to environmental cues and stress, and CBD was able to decrease the heroin relapse behavior in rats, so we decided to study that in our human heroin users,” Hurd said. First, Hurd’s team conducted a successful phase 1 clinical trial to evaluate CBD’s safety.They next conducted a small phase 2 trial and saw that, as in rats, CBD decreased heroin-seeking behavior in humans, even long after it had been metabolized and eliminated from the body (6) .

Hurd is now investigating whether CBD could be leveraged to treat addiction . “I’m not saying that marijuana is a treatment for the opioid addiction epidemic, but CBD might be,” emphasized Hurd. “Before calling it medical marijuana, we actually need to carry out the studies to understand what component of the plant, or combination of components, is truly medicinal for specific symptoms. We need a lot more research.”