Monitoring local antimicrobial resistance prevalence using honey bees

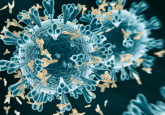

Honey bees show promise as biomonitors for tracking the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) within their local environment.

Researchers at Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia) have demonstrated the potential of honey bees as a ’crowdsourced’ environmental proxy to monitor the prevalence of AMR targets and environmental contaminants. The research, led by Mark Taylor, highlights that our understanding of AMR prevalence, one of the most serious emerging challenges to human health worldwide, remains incomplete.

Honey bees possess several qualities that make them promising candidate biomonitors. This is because colonies that forage close to or within urban areas are in proximity to human populations so they interact with many of the same pollutants. And, “bees only live for about 4 weeks, so whatever you’re seeing in a bee is something that is in the environment right now,” explained first author Kara Fry.

The researchers examined the gut contents of honey bees sourced from 18 hives located across the Greater Sydney area, with sites selected to provide a range of land used for industrial, residential and rural purposes.

They studied the presence of trace contaminants and Class 1 integrons, genetic elements that are amongst the most frequently observed drivers of AMR gene transfer. Eight bees were analyzed per hive. 83% of the studied bees contained one or more AMR targets with similar frequencies observed independently of land use.

How are microbes affected by human-induced environmental change?

How are microbes affected by human-induced environmental change?

Soil prokaryotes involved in key ecological processes tend to need specific conditions to survive.

One notable finding was the correlation between the prevalence of AMR targets and the area of local waterbodies within foraging distance of the hive, contrasting with the researcher’s initial hypothesis that more resistance genes would be found in more densely populated areas due to proximity to human populations. “We suspect the presence of local water bodies that collect run-off is a critical source of AMR contamination,” commented Fry.

The researchers also identified a correlation between lead concentration and population density, as well as a correlation between the proportion of industrial land usage and the concentration of the inorganic trace contaminants iron, lead and vanadium.

The degree to which AMR targets were widespread across all sampling sites concerned the researchers and should serve as a warning. “The main drivers of AMR are the misuse and overuse of antimicrobial products,” Fry explained. “The message from this research reinforces the need to use antibiotics when needed and as directed, and to dispose of them appropriately by returning unused medicines to your pharmacy,” and to avoid using products in our homes with added antimicrobial agents.

The study highlights the potential for utilizing honey bees to create monitoring networks to quantify the spread of environmental contaminants and AMR prevalence. The researchers hope to investigate the potential inclusion of bird species for monitoring environmental contamination, as well as further investigation into the range of contaminants that can viably be detected with honey bees.