Lab-grown mini tumors: a more accurate prediction of cancer treatment response than DNA analysis?

Researchers successfully used lab-grown mini replica cancer tumors to predict a patient’s response to different treatments.

A team from the Institute of Cancer Research (London, UK) and the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK) grew mini cancer tumors to test different treatments, predicting a patient’s response. The hope is that in the future, this method will become common place, enabling doctors to personalize a patient’s treatment course, cutting down time wasted trialing treatments that ultimately do not work and hastening recovery.

The study, published in Science, relied on biopsy samples from 71 people with advanced bowel, gastro-esophageal or bile duct cancers, whose tumors had spread around their body.

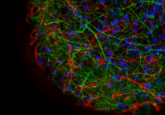

The researchers used cells from the biopsy samples to grow the replica tumors, placing them on a gel and allowing them to form a 3D shape. They tested the replicas with 55 different cancer treatments and compared the results to how the patient actually responded to the treatment.

This method was 100% accurate at determining which treatments wouldn’t work and 88% accurate at choosing a treatment that would shrink the tumor in the cancer patient.

“We found that recreating patients’ tumours in the laboratory using this new technique gave us an extremely promising way to predict whether a drug would work for a patient,” explained study leader Nicola Valeri from the Institute of Cancer Research, UK. “We were able to look in incredible detail at how tumours responded to drugs – including patterns of gene activity and mutation, and even how the cancer would evolve in response to treatment. We looked at tumours from patients with cancers of the digestive system, but the technique could be applied to a wide variety of cancer types.”

Replica tumors were 96% identical to the original tumors, including containing a similar mix of different cell types as did their parent tumors and the possessing the same pattern of genetic mutations.

“This study has shown that testing drugs on replica tumours before they are given to patients is not only possible, but predicts how a patient will respond more accurately than simply looking at the cancer’s DNA,” commented study co-author, Paul Workman. “The potential of mini tumours doesn’t stop there. Having a better model for how cancers may respond to treatment could help accelerate drug discovery and even reduce reliance on animal experiments.”

The researchers hope that the models will not only be used to personalize cancer treatments for patients, placing less emphasis on a “trial and error” approach, but also guide the development of new drugs. On top of that, it is hoped the use of a new model for how cancer tumors respond to treatments will reduce reliance on animal models.