Expanding the hygiene hypothesis

A recent study shows that we are becoming more susceptible to chronic inflammatory diseases, allergies and mental health disorders, seemingly supporting the ‘hygiene hypothesis’.

As humanity has evolved, it has continuously developed systems and processes to seemingly make life more convenient and safer. However, as these systems develop and progress they can lead to end results that are less than beneficial to our species: the convenience of travel and energy production reliant on the use of combustion engines has increased air pollution; damaging our lungs and changing the climate around us to become hostile to human life, fast food contributes to the ever-advancing obesity crisis and the sterility of our living environments could be leading to something known as the ‘hygiene hypothesis’.

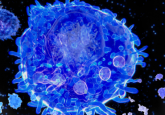

The last of these points is the theory that as we are naturally exposed to fewer pathogens and microbes, encountering others later in life than previously would have been possible, the prevalence of chronic inflammatory diseases (CID), mental health disorders and allergies are increasing.

“The human immune system acts like a switchboard between somatic and psychic processes. The study results [sic] help us understand why many people who do not have a history of psychosocial trauma get afflicted by mental disorders and, conversely, why traumatized people show a predisposition to chronic inflammatory diseases.”

A team of researchers from the University of Zurich (UoZ, Switzerland) and the University of Lausanne (Switzerland) led by Vladeta Ajdacic-Gross (UoZ) took inspiration from the hygiene hypothesis, analyzing a cohort of 4874 people between the ages of 35–82 to examine the co-incidence of diseases or disorders in childhood. Latent class analysis was used to analyze the epidemiological data from the cohort.

Using early morbidity patterns, biomarkers; such as white blood cell count and inflammatory markers, and association with CID and psychiatric disorders during adulthood, the cohort was divided into five subsections. The largest, consisting of 60% of the group, were classified as having a “neutral” immune system. This group had a low disease burden in childhood, though, not as low as the next largest group, classified as having a “resilient” immune system, which consisted of 20% of the cohort.

The remaining 20% of the cohort consisted of an “atopic” group (7%) who experience multiple allergic diseases, a “mixed” group (9%), afflicted by a single allergic disease and a bacterial-rash-inducing disease, and a final group who had experienced trauma in childhood (5%) and were more susceptible to allergic disorders than the neutral group but not to common childhood diseases.

-

The hygiene hypothesis: how gut microbes arm us against autoimmunity

-

Diet changes long-term immunity

-

Have allergies? Stay away from mice

Further analysis of these subdivisions showed that those born earlier in the 20th Century were more likely to be included in the resilient or neutral groups than those born later, seemingly validating the hygiene hypothesis. “Our study thus corroborates the hygiene hypothesis, but at the same time goes beyond it,” opined Ajdacic-Gross.

The immune classifications were shown to impart a prophetic value to each cohort’s health in the later stages of life. The resilient group were less likely to develop CIDs and psychiatric disorders, while the atopic and mixed groups experienced elevated rates of somatic and mental health disorders. The group who had experienced trauma were also more likely to be affected by mental health disorders and, in women, CID.

Summarizing the results of the study, Ajdacic-Gross explained that they, “indicate that the human immune system acts like a switchboard between somatic and psychic processes. They help us understand why many people who do not have a history of psychosocial trauma get afflicted by mental disorders and, conversely, why traumatized people show a predisposition to chronic inflammatory diseases.”